From 1836 to 1971, all types of men and women arrived and left Frankfort from the railroad passenger station on Broadway. The depot was located between High and Ann streets and was home to three railroads — Louisville & Nashville Railroad, Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and Frankfort & Cincinnati Railroad.

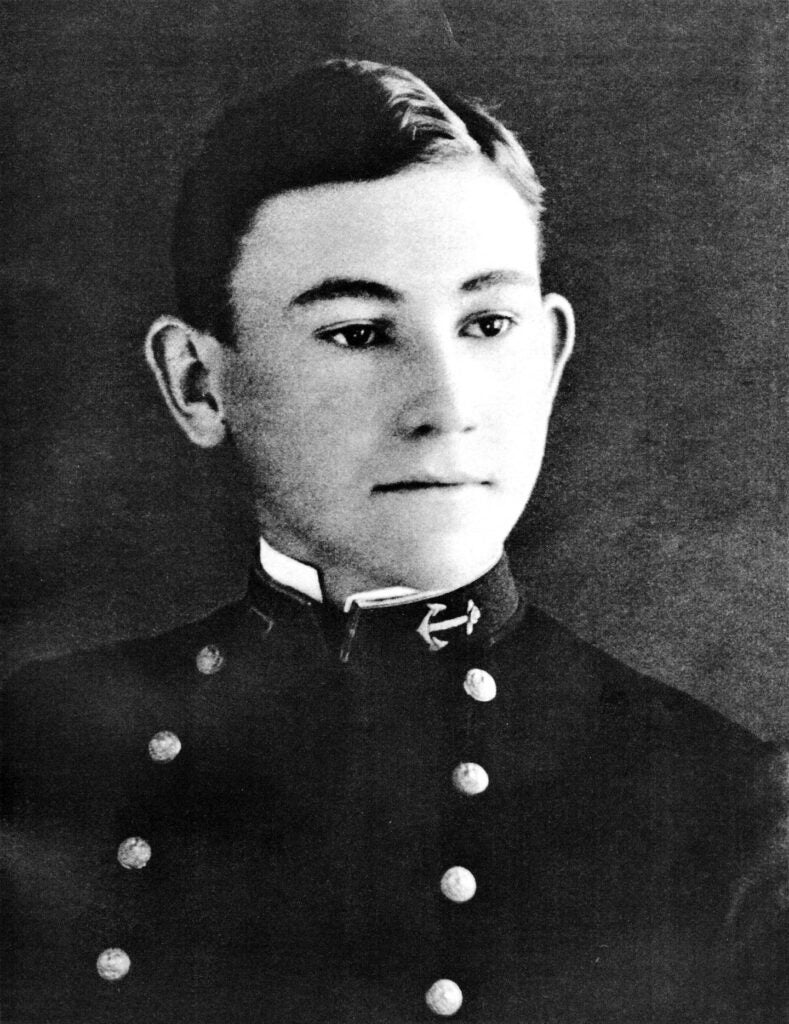

Among those who passed through the Frankfort railroad depot to ride a train to the great outside world was a 17-year-old boy from Owen County. He was born in 1888 in Natlee, a small village on the east edge of Owen County. Shortly after his birth, his father was elected Owen County Judge, and the family moved to Owenton. After a term as county judge, his father hung out his shingle as a lawyer in Owenton.

In 1904, the young man, not yet a high school graduate, was awarded an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy. He and his parents traveled by carriage from Owenton to Gratz, then on the Kentucky River where they caught a packet boat to Frankfort. At Frankfort, they walked from the public landing to the Frankfort train depot. There the parents purchased tickets for their son to ride the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway’s Fast Flying Virginian passenger train to Washington, D.C., and then on to Annapolis. Thereafter over the years, this Owen County native would arrive and depart from the Frankfort depot when he came home to visit his family.

During his time at Annapolis, he was an average student, but he could outshoot anyone on the pistol or rifle range. He won numerous shooting medals and trophies, including gold medals at the 1920 Olympics. These medals are now housed at the Kentucky Historical Society. Upon graduation from Annapolis, he went to sea as an Ensign. His leadership abilities soon caught the attention of the Navy, and he rose steadily in grade until 1942 when he was promoted to Rear Admiral.

In 1942, with the war in the Pacific becoming a test of wills between the United States and Japan, he was put in command of a task force built around the battleships Washington and South Dakota. During the night of November 14, 1942, he sailed his ships through the waters off of Guadalcanal to meet an oncoming Japanese naval force. His ships had to cross Iron Bottom Bay before they could head up the Slot to contest the latest run of the Tokyo Express that was bringing supplies down from Rabual to help sustain the Japanese troops fighting on Guadalcanal. Leading the Japanese resupply convoys was the battle ship Kirishima.

As the American battleships crossed Iron Bottom Bay, they were spotted by patrolling U.S. Navy PT Boats (Peter Tars). The Admiral, overhearing the PT Boats talking on their between-ship radios that they were planning on launching a torpedo attack on his battleships, thus setting up a Blue-on-Blue engagement, broadcast in the clear the following, “Peter Tar, Peter Tar, this is Ching Lee, Chinese, Ching Lee, catchee?” Upon hearing this message, the PT Boats turned away, and the Admiral and his ships sailed on up the Slot to confront the Japanese in a brutal night fight. During the battle, the Japanese inflicted more damage than they received, but their supply run was broken up and they turned back without completing their resupply mission.

Following this successful engagement, the Rear Admiral continued his climb up through high command. By 1944, he was a Vice Admiral, commanding Task Force 34 (TF 34), the fast battleships. In October 1944, TF 34 was operating under Admiral Halsey’s command when the aircraft of the 3rd fleet engaged the Japanese warships trying to transit San Bernardino Strait and attack the American transports unloading assault troops on Leyte. The Japanese surface vessels were heavily damaged by the attacking 3rd Fleet aircraft and, as a result, turned and steamed away from the Philippines. Admiral Halsey then took his fleet north to engage a Japanese carrier force moving south from Japan. As he went north, Halsey took TF 34 with him, leaving San Bernardino Strait unguarded.

After Admiral Halsey led the 3rd Fleet north away from San Bernardino Strait, the Japanese surface units turned and re-entered the Strait. After transiting it, they steamed south for the American transports in Leyte Gulf. Along the way they encountered Task Unit 77.4.3, Taffy 3, consisting of six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. In a gun and air battle that still has historians trying to reason out how and why the American ships, so heavily out gunned, survived, the Japanese ships turned and again retreated north.

Admiral Nimitz, commanding the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, was perplexed that the fast battleships of TF 34 were not intervening to help Taffy 3. Wanting to know where the fast battleships were, led Nimitz to send one of the more famous messages of World War II. It read, “Where is, rpt, where is Task Force Thirty four, the world wonders?”

As a result of this message, Admiral Halsey, with the Japanese carriers almost in sight, ordered TF 34 to turn back for San Bernardino Strait. The result would be that the fast battleships would not reach San Bernardino Strait until long after the Japanese fleet had retreated through these waters and also missed out on the destruction of the Japanese carriers.

The April 1945 Okinawa Campaign saw the Japanese committing their Kamikaze aircraft to hit and sink the U.S. Navy carriers supporting the American ground actions on Okinawa. The fast battleships, as a result of the Kamikaze aircraft, moved close to the carriers so as to allow their enormous anti-aircraft gunfire to be used to protect the carriers from the final dive of the Kamikaze aircraft. By the end of the Okinawa Campaign, the Admiral was tired and in need of rest. He was brought stateside in August 1945 and given a staff position, but the strain of war had been too great. Before the year was over, he was dead.

The U.S. Navy in 1954, in recognition of the service this man from Owen County had rendered to his country, named a ship after him, USS Willis A Lee DD 929.

The Capital City Museum is always interested in recording the stories of those who used the Frankfort depot to travel to other cities and towns or to reach Frankfort to shop or find a new home.