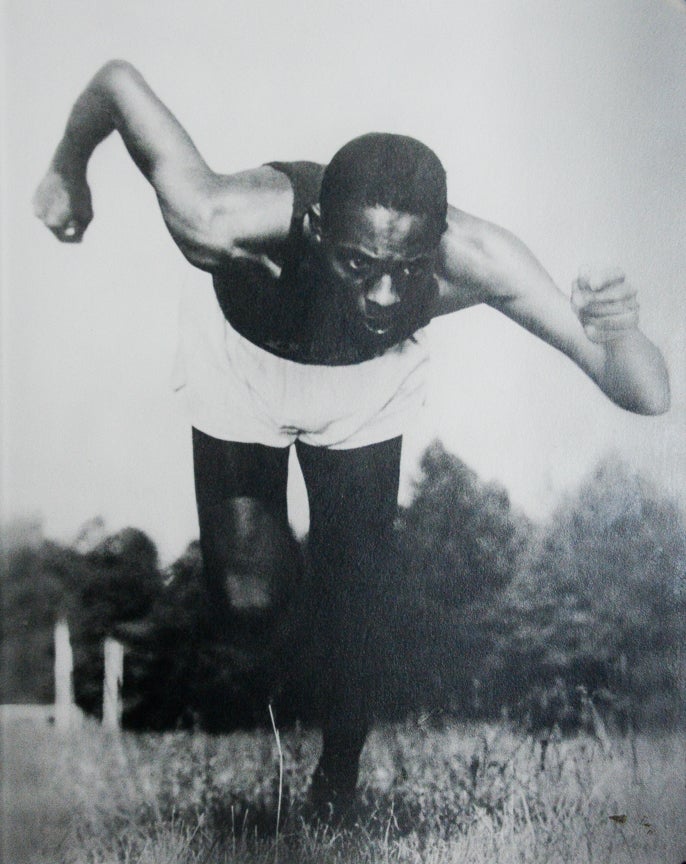

Ken Gibson’s track career has sent him all over the world, garnered national championships and landed him in numerous halls of fame.

And it all started with swim trunks and tennis shoes.

Running in a track meet at the end of the school year, Gibson received encouragement from a friend who wanted Gibson to run in some summer track meets.

“He said ‘I’ll be coming to get you,’” Gibson recalled. “I forgot all about it. A week later there was a knock on my door and he asked if I was ready to go.”

Gibson wasn’t, but he quickly changed into swim trunks and Converse tennis shoes.

“That’s all I had,” he said.

It was enough.

Gibson finished third in the meet, qualifying him for the city championships, and he placed third in that meet, too.

“I went out and did a lot of running,” he said. “I didn’t know what I was doing; I didn’t have a coach.”

Those races started Gibson, who’ll turn 84 on Feb. 19, on a path he would travel for the rest of his life.

He’s coached high school track, at the college level and was on the U.S. Olympics coaching staff in 1988. He also served as an adjunct professor at Georgetown College for 19 years.

Gibson, who lives in west Frankfort with his wife, Betty, coached Kentucky State men’s track team to an NCAA Div. II national championship in 1971, and in 1985 he became the first African-American head coach hired at the University of Mississippi.

Early years

Gibson grew up in Brooklyn at a time when New York City had three professional baseball and football teams.

“You couldn’t help but be a sports fan,” he said. “We played baseball, basketball, some touch football. The New York Police Athletic League had activities for youth, basketball, baseball, boxing, track, anything of that nature. “Everyone got in the ring once or twice, but if you got hit in the face too many times you said ‘I don’t want to box.’”

Knee problems kept Gibson off the track until just before he began high school, when he ran in the city championships and finished third. Summer track meets were put on by the Police Athletic League and New York City Parks Department.

“I went to high school, went out for the track team and that was it,” Gibson said.

After graduation Gibson went to Indiana University, where he was a sprinter on the track team.

His senior year at IU, Gibson added cross country to his repertoire.

“I was one of the first sprinters to run cross country and then go back to running sprints again,” he said.

Gibson graduated from IU with a degree in biology in 1955 and then spent two years in the military.

“I was in condition,” he said about basic training. “It wasn’t much of a problem for me. With the physical part of training, cross country really paid off.”

After his stint in the military, Gibson returned to IU for his master’s degree.

“The (track) coach asked what I was doing,” Gibson said. “He asked if I wanted to help, and I said sure. I’d be at practice every day, learning. I was getting up to speed on things like field events, things I didn’t compete in. I was getting ready to be a coach.”

In 1958, Indiana’s head track coach and his assistant were going to be out of town for the week of spring break.

“They left me to conduct practices and hand out the per diems so they’d have money to eat,” Gibson said. “I told them ‘you don’t come to practice, you don’t eat.’

“The next week we had a meet, and the ones who stayed with me and worked during spring break brought home the most goodies.”

Coaching starts

After getting his master’s degree from IU, Gibson returned to New York to teach and coach.

“It was rough at first,” he said. “I couldn’t get a job. I’d apply for jobs that were posted, but when I showed up they were taken. I went and saw the basketball coach at my old high school, and he asked what I was doing. I said looking for a job, and he asked what my degree was in. I told him biology with a minor in physical education.

The coach told Giben that he would call a principal at a junior high school that had an opening.

“He called me the next day, and I started working. Sometimes it’s not what you know but who you know,” Gibson recalled.

While teaching in junior high, Gibson was working with the track team at his old high school when the head coach took another position.

“I took it over in March,” he said. “I took a different approach. The first week of practice they didn’t see the track. I’d take them to the park and tell them to take off. They ran around a lake, getting in condition.

“We won the Brooklyn championships, and we hadn’t won that in a couple of years. Things took off.”

From 1961-64 Gibson’s teams won three indoor city championships, three outdoor city championships, and four outdoor Brooklyn championships. There were no indoor Brooklyn championships.

National championship

Gibson moved to the college level, serving as head coach at Florida A&M and Grambling State before coming to Kentucky State.

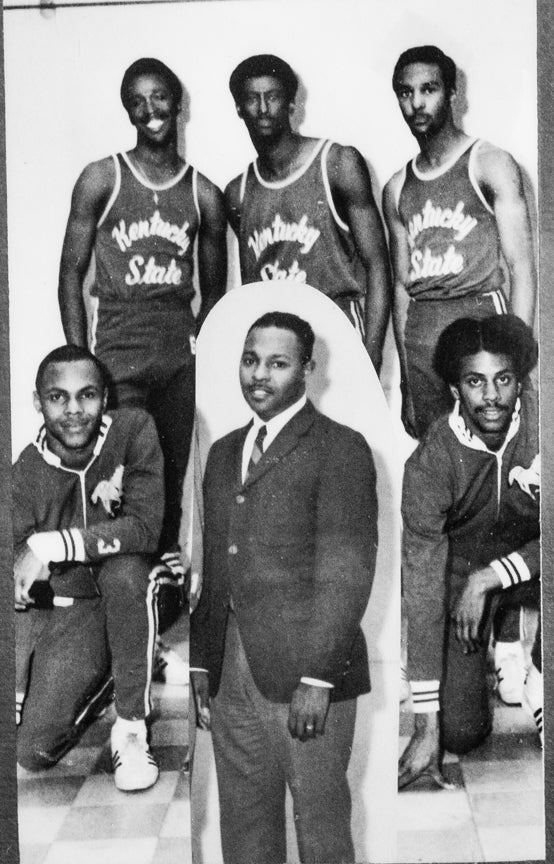

In 1971, the Thorobreds won the NCAA Division II national championship with five athletes.

On the first day, KSU’s Dick Garrett won the 100-yard dash, Steve Jordan won the 400, the 4×1 relay finished second, and Garrett finished second in the 200.

“A coach called me after the first day and said, ‘It looks like you have the meet in the bag,’” Gibson said.

“We won with 40 points or something like that with five guys. The team that was expected to win, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, had 30 kids and was the host school.”

Gibson had five individual national champions at KSU in addition to the national championship team.

Education

For Gibson, coaching wasn’t just about athletics. While teaching at the high school level, runners began talking to him about continuing their education and athletic careers.

“‘Coach, I’m thinking about college,’ they’d say to me,” Gibson said. “I was a college graduate. I made the swing through the East Coast schools and the historically black colleges, Johnson C. Smith, Fayetteville State, Virginia State, North Carolina Central. I had one runner go to Harvard. It got to the point if you weren’t interested in college, don’t come out for the track team. You had to be up in books and things like that. You had to have something concrete in the future.”

Education is something valued by the Gibson family.

Betty Gibson, Ken Gibson’s wife of 57 years, is a retired teacher. Their son, Tracy, teaches and coaches track and football in St. Louis, and their daughter, Tamara, is a guidance counselor in the Virginia Beach, Virginia, school system.

Gibson received his doctorate from Brigham Young University in 1978.

Track honors

Gibson has been inducted into several halls of fame, including the KSU Hall of Fame in 2003 and the USTFCCCA Hall of Fame in 2004.

He was also member of the coaching staff for the U.S. track and field team at the 1988 Olympics, and he’s served as an official at numerous Olympic Games and Olympic Trials.

Gibson was a staff member for numerous international teams, including head coach of the 1997 USA World Indoor Championship team.

He conducted a three-week clinic in China in 1989, teaching coaches and conducting clinics, and in 2010 went to Nigeria for three weeks to work with coaches and athletes.

Gibson’s last collegiate coaching stop was at the University of Mississippi.

Hired in 1985, he was one of the first African-Americans, if not the first, to be hired as a head coach at a Southeastern Conference school.

“A story said I was the first African-American hired as a head coach for a specific position,” Gibson said. “Fletcher Carr was an assistant coach at Kentucky, and he was the wrestling coach there. When Arkansas joined the SEC, Nolan Richardson was the men’s basketball coach.”

Gibson stayed at Ole Miss for three years.

“I would have liked to stay longer,” Gibson said, “but we couldn’t find a job for my wife. We’d been married 20-some years, and that was not going to end.”

As far as issues with being the school’s first African-American head coach, Gibson said he didn’t have many.

“I didn’t have any problems,” he said. “The only problem I had was I didn’t have enough staff to run a competitive SEC program. I had one graduate assistant and one assistant.

“And the rebel flag was flying kind of free. There was one athlete I was trying to recruit. His father said he left Mississippi when he was 5 years old, and he wasn’t coming back until he had to bury his dad. You ran into that sometimes.”

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Mexico City Olympics, where two African-American track athletes, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, raised clenched fists during a medal ceremony.

The demonstration set off a furor across the country.

“They are two very good friends of mine,” Gibson said. “What a lot of people don’t realize is after that demonstration things changed. Big schools started hiring black coaches as assistant coaches and later as head coaches.”

That included Gibson.