Everyone in town knows that if you want to find out anything about Frankfort, contact Russ Hatter at the Capital City Museum.

“A lady contacted me, she has a relative buried in the confederate cemetery section at the Frankfort Cemetery and she’s wanting to know more about him, so now I’m looking into locating that person for them,” Russ said.

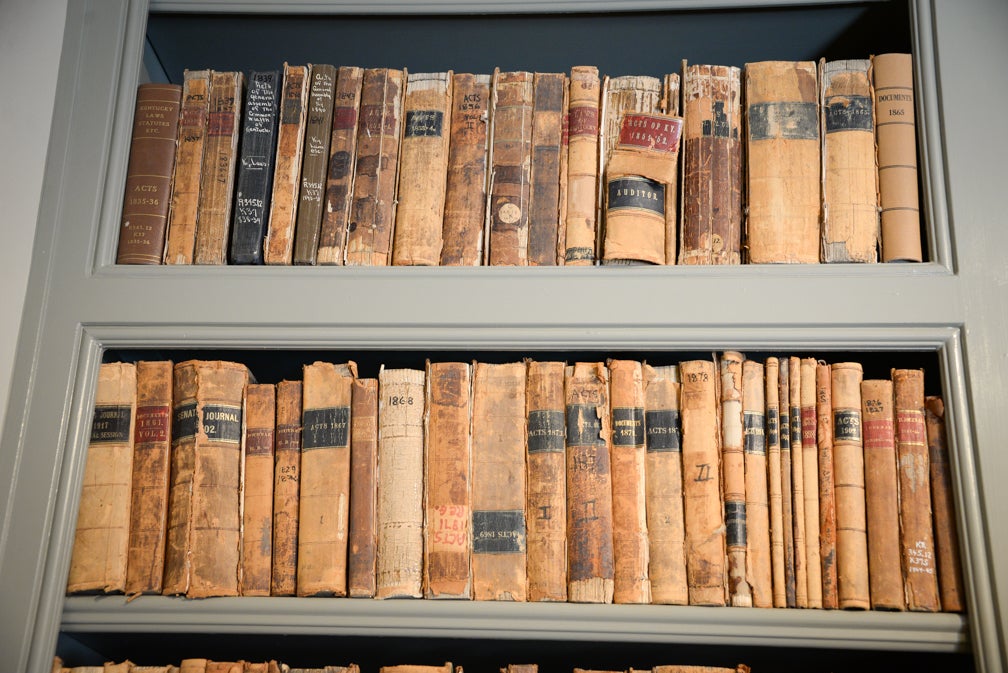

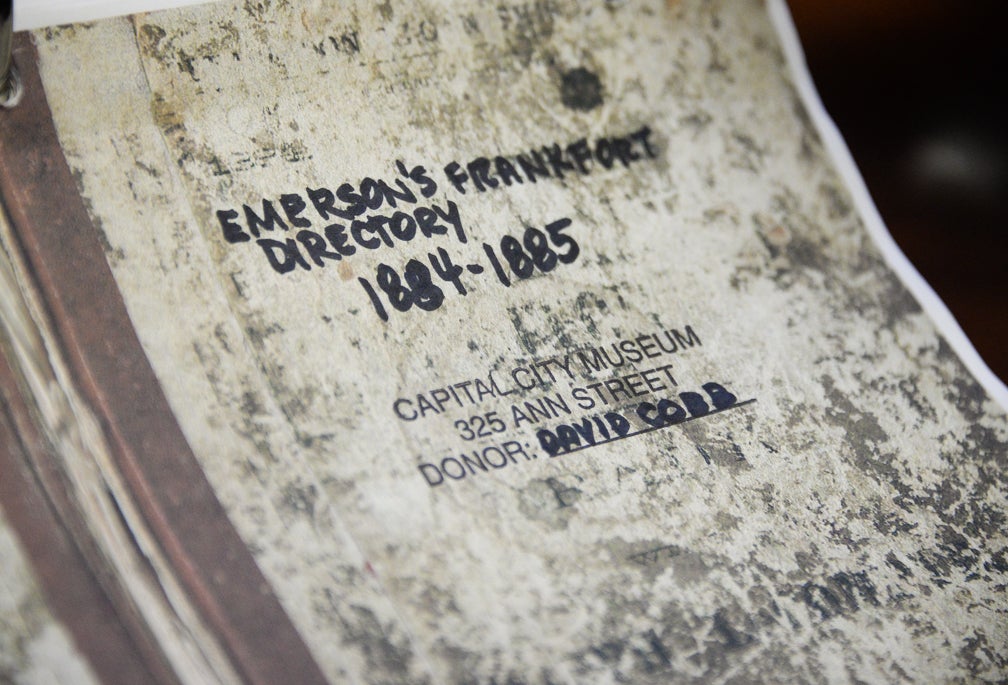

He first starts with doing a street search in the city directories at the museum that date back to 1884.

I can find where people lived and worked,” he said.

He has answered numerous calls like that over the years. When he digs up information for people, that’s when he strikes gold finding events from history that he’s really interested in.

He loves when he discovers stories of murder in Frankfort’s history. One of his favorite stories is of the killing of Salom P. Sharp in 1812. The murder was so famous for it’s time that Edgar Allan Poe wrote a play about it. A man and his wife were convicted for killing Sharp and while in prison they drank poison in an attempt to commit suicide together. When it didn’t work, they tried to stab themselves. She died, but he didn’t and was hung for the crime.

“I’m fascinated by these stories,” Russ said.

So fascinated, that he’s gathered more than 30 murder stories — including another about a serial killer that murdered butchers in Frankfort — and developed a walking Murder and Mayhem tour that he does every October.

Russ currently serves as the city historian, but has held different positions at the museum over the years since he helped to found it in 2005. Along with former longtime director of the museum Nicky Hughes, now retired, Russ helped to research and curate many of the museum’s exhibits.

The museum is now closed because of the coronavirus pandemic, but Russ hopes it will reopen in the summer. Since being closed, the museum, which is operated by Frankfort Parks, Recreation and Historic Sites, has undergone renovations under the leadership of Penny Peavler, an arts administrator who has been conducting a facility audit, assisting with the physical renovation and strategic planning and visioning at the museum with the Capital City Advisory Board.

“Our mission to, ‘instill pride in our community by sharing the stories of our rich history and culture through research, education and preservation’ is coming to life in a very real way through the renovation of our building and new and enhanced interpretive exhibits,” Penny wrote in an email.

Penny said when the museum safely reopens, one of the signature exhibits about what makes the community so special will be the Frankfort Fishing Reel exhibit.

“Frankfort is home to four of the most famous baitcasting reels,” Russ said.

Stated in a former State Journal article written about the exhibit, in 1832, Frankfort jewelers and silversmiths refined the technology, using precision tools and superior materials to perfect the reels sought after and owned by presidents like William Howard Taft, William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt.

Judge Mason Brown asked local jeweler and silversmith Jonathan Meek to fix his baitcasting reel and, without any intention of making such products for commerce, Meek obliged. The craftsmanship of Meek’s reel baited interest with orders for more. His brother Benjamin Meek and apprentice Benjamin Milam took over the work by producing handcrafted reels. The success was tied to the Meek & Milam store on West Main Street.

The reels weren’t for the common citizen. They cost the equivalent of a soldier’s wages for an entire month in the 1830s.

Called the “Milam” and “The Frankfort, Kentucky, Reel,” manufactured by B.C. Milam and Son, the reels won three international first prizes and medals, including at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, the Fisheries’ Exposition in Bergen, Norway, in 1898 and the 1900 World’s Exposition in Paris, France.

Frankfort became a place known not just as the capital of Kentucky, but as a place where the coveted reels were crafted.

When the Meeks decided to get out of the reel-making business, the same metal working lathe was used by B.C. Milam and was later purchased by Clarence Gayle, whose father was an apprentice at Meek & Milam.

Along with the fishing reels, the exhibit also includes Meek’s 1852 chronometer.

According to research done by the exhibit coordinators Betty Barr and Don Kleier of Frankfort, on Sept. 11, 1942, Gayle was quoted in saying, “I recollect very distinctly the chronometer that you refer to, as Mr. Meek had it in his jewelry shop all of the time. It was a custom back in those days for every watchmaker or jeweler to make himself a regulator and often a chronometer as evidence of his skill and ability as a fine workman.”

For that reason, the research states, the chronometer on exhibit is not numbered. It was a single entity made by a highly skilled horologist and craftsman as his personal statement. Mass production for public sale was not to be, making the chronometer a single, one-of-a kind work of art.

Renovations

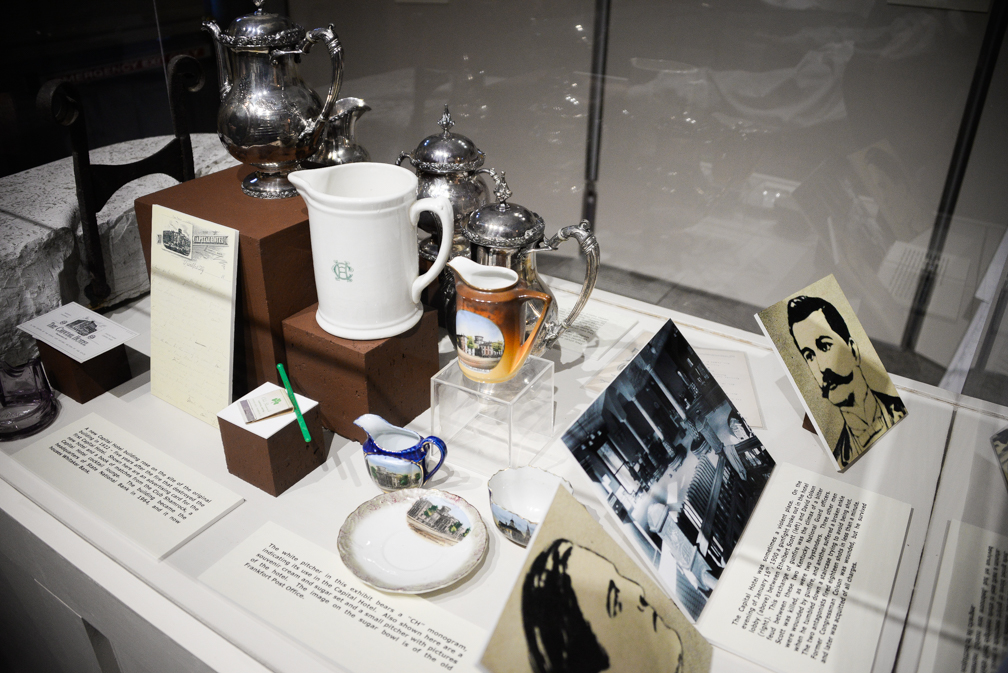

During the closure, renovations have been made to the visitor center and retail space. Penny said that there is also a gallery dedicated to telling the stories of how Frankfort came to be the capital of Kentucky. Other exhibits include Kentucky Stays in the Union, Frankfort’s Citizens Famous and Ordinary, Frankfort Industry, bourbon history and more.

Penny said renovations also included a new library and meeting and program space, an exhibit about Frankfort restaurants of the past that is set in the 1950s and includes a children’s kitchen area and a planned small exhibit of original Paul Sawyier paintings.

She said there will also be a new exhibit about the history of African Americans in Frankfort. The exhibit is being created by a group of community volunteers, led by board member Sheila Mason Burton, which is ensuring it has an authentic voice, she said.

“The exhibit will explore churches, schools, neighborhoods and businesses,” Penny said.

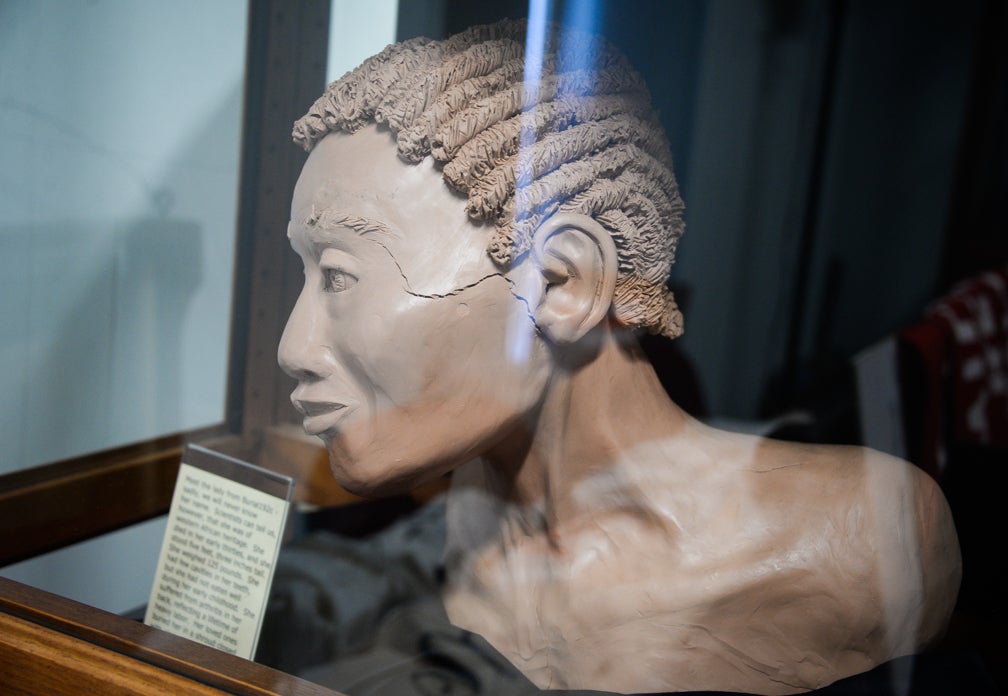

Another exhibit is of Frankfort forgotten cemetery. Russ said in the early 2000s when they were building the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet on Mero Street, crews discovered about 250 bodies.

“That was Frankfort’s original cemetery at the end of Ann Street,” he said.

The bodies were left behind in 1844 when they moved the city cemetery to its current location on East Main Street. The bones were sent to the University of Kentucky to be examined.

“They gave us buttons and nails, so we can have them on exhibit,” Russ said.

The museum was also given cast models of what some of the people would have looked like. Most of the bones were African American, Russ said.

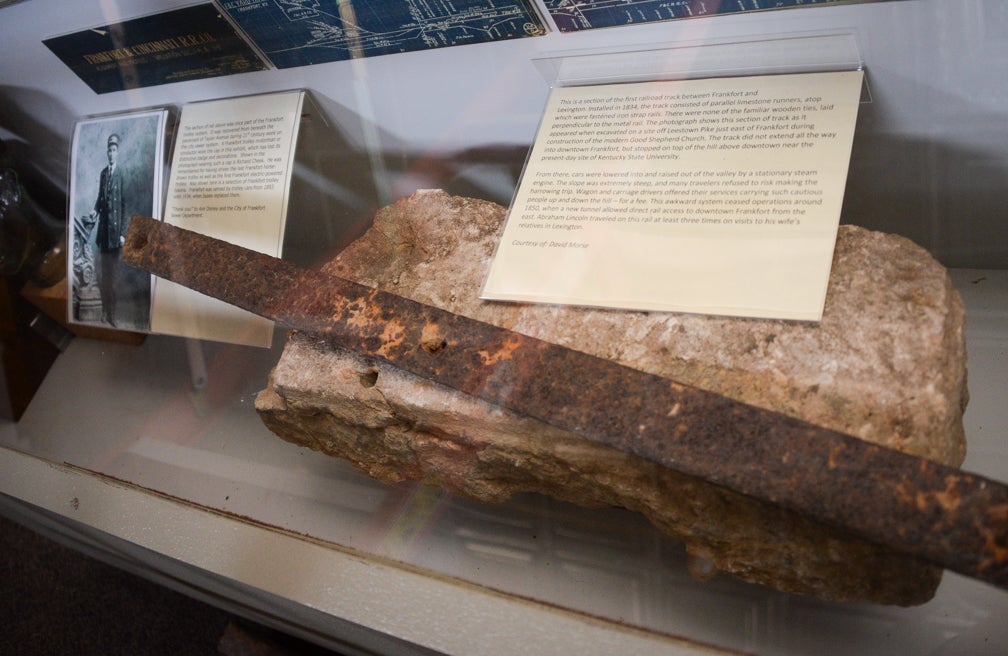

All of the items on exhibit have been donated to the museum including a railroad sill that would have been in place when Abraham Lincoln rode through town to visit his wife’s family in Lexington.

Another prized donation is a Civil War era American flag that is framed and hangs on a wall in the museum. A man who bought an old brick house on Third Street donated the flag in 2005. The house had been owned by John LaFayette Scott who he was a strong Union supporter during the Civil War. The man found the flag stuffed into a windowsill in the attic of the home, likely done to block wind, Russ said.

“A newspaper account tells of them putting a new flag that John LaFayette Scott had made on the Old Capitol,” Russ said. “We don’t know for sure if this was the same flag.”

However, they know the flag is from the Civil War era because there are 34 stars on it.

Russ is also always excited to show off the office of Dr. E. E. Hume, the doctor who treated former Sen. William Goebel immediately after he’d been shot in front of the Old Capitol. The scene has been recreated in Hume’s original office which is located on the first floor of the museum.

Until the museum is reopened, Russ will continue his research on the various points in Frankfort’s history highlighted in the exhibits. He will also continue to help people who are researching Frankfort’s history.

To help those people, Russ is working on a timeline that begins in 1750 and tells of the main events that occurred in Frankfort, Central Kentucky and the world during the given year they are researching.

“It’s so that people have reference as to what was going on in the world compared to Kentucky for whatever they’re writing about,” he said.

Russ loves to help people find whatever it is they are looking for and he always seeks to help them find the facts.

“I love to reinforce the truths as opposed by the myths,” he said. “I want the truth. I think we should know the truth. Truth is important.”