By Daksha Pillai,

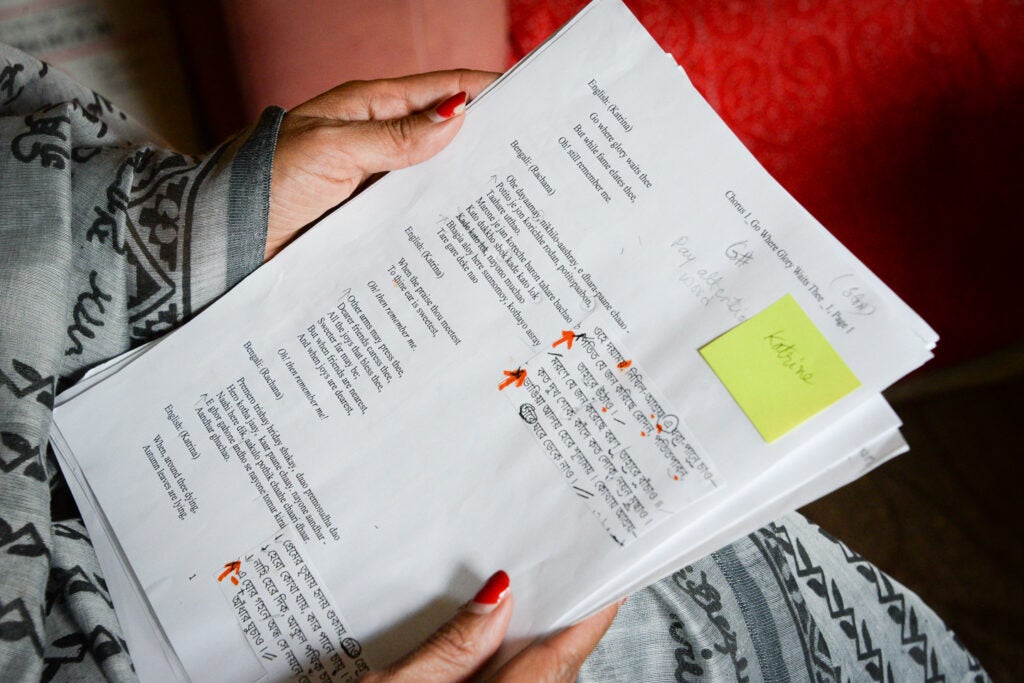

To a stranger, this yellowed folder might seem like a prime candidate for the recycling bin. Stuffed to the brim with tattered papers, shedding paperclips and post-it notes, it’s unclear what exactly this is meant for — after all, the verses scrawled across its pages are not even in the same language.

In reality, this folder represents the culmination of a woman’s life-long dream, an artistic calling that crossed oceans, survived decades of waiting and refused to be deferred.

Rachana Rahman was born in Bangladesh to a family where creativity was as abundant as the country’s lush greenery. Instead of playing games outside, she and her siblings would organize amateur theater productions for the village children.

Rachana Rahman looks at the lyrics of a song written in both English and Bengali from her album “Under the Western Sun.” Bengali. (Photo by Hannah Brown)

“I think creativity is in my genes,” Rachana said.

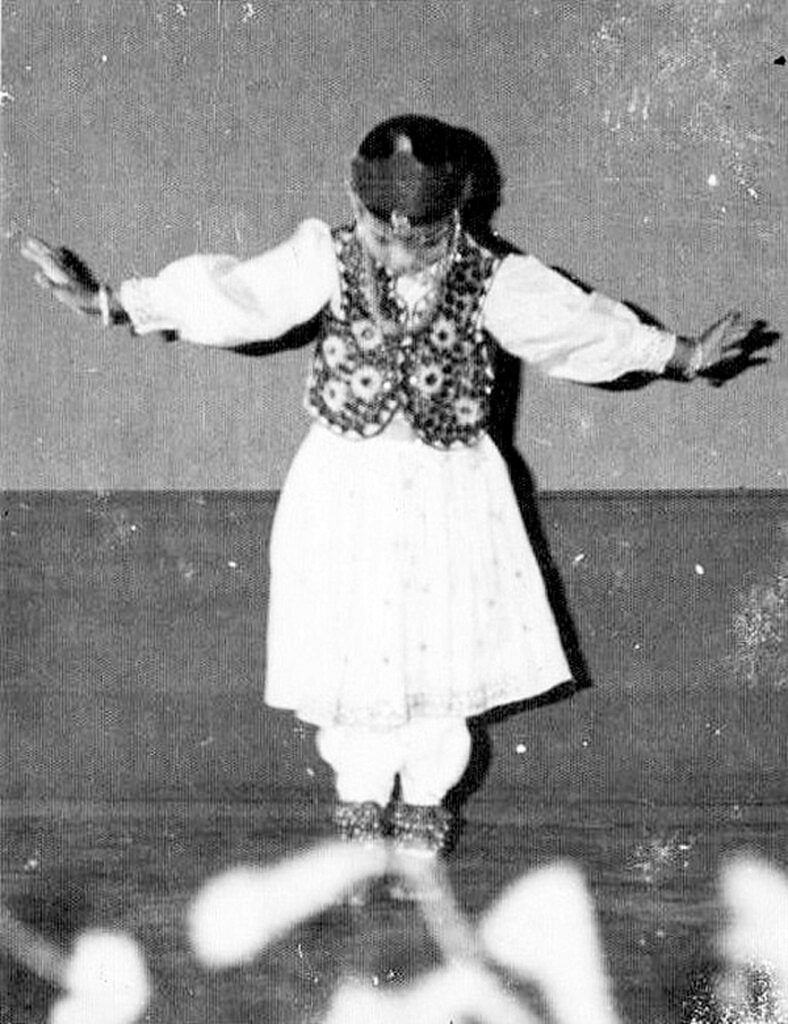

Rachana’s first artistic love was Kathak, a classical Indian dance style that conveys stories through expressive hand and footwork. But when she contracted a bout of rheumatic fever, her professional dancing dreams had to be set aside.

To help Rachana cope, her mother encouraged her to turn to vocal music and acting. She became so enthralled by the latter that she deliberately failed the entrance exams for engineering and medical school so that her only option would be to attend theater school.

Though she loved acting, it was difficult for her conservative Bengali community to understand her passion. Villagers would linger at their doorsteps and windows when she came home late at night from her theater school, whispering about her reputation. Even for her progressive family, the scrutiny eventually became too much to bear.

Before Rachana could graduate from theater school, her parents introduced her to a handsome Bengali man studying Environmental Engineering in the U.S. Three days later, they were married.

From the outside, Rachana’s arrival in Frankfort seemed to mark the end of the artistic dreams of her youth. In 1995, she moved to Kentucky and in 1999 her son, Monon, was born and she began as a student at Kentucky State University and finished with a degree in computer science. Working as a software engineer by day and running a household by night, there was scarce time left over to devote to art.

But even as her life changed, Rachana held strong to her dreams. The free-wheeling pursuits of her youth coalesced into one chief ambition: to attend Visva-Bharati University in India, founded by Rabindranath Tagore.

Like many other Bengalis, Tagore was a fixture in Rachana’s life since she was born. The defining figure of modern South Asian literature, Tagore was recognized worldwide for his moving poetry, receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 for his collection Gitanjali. But in Bangladesh and West Bengal, this international acclaim pales in comparison to the deep hearted reverence felt by Tagore’s own people.

“If anyone loves Tagore and his song, they cannot be a bad person,” Rachana said.

By that logic, Visva-Bharati was nothing short of heaven on earth. But like any paradise, the journey there seemed impossible.

“Everyone thought I was crazy. They always asked me ‘how could you leave your husband and son alone?’,” Rachana said.

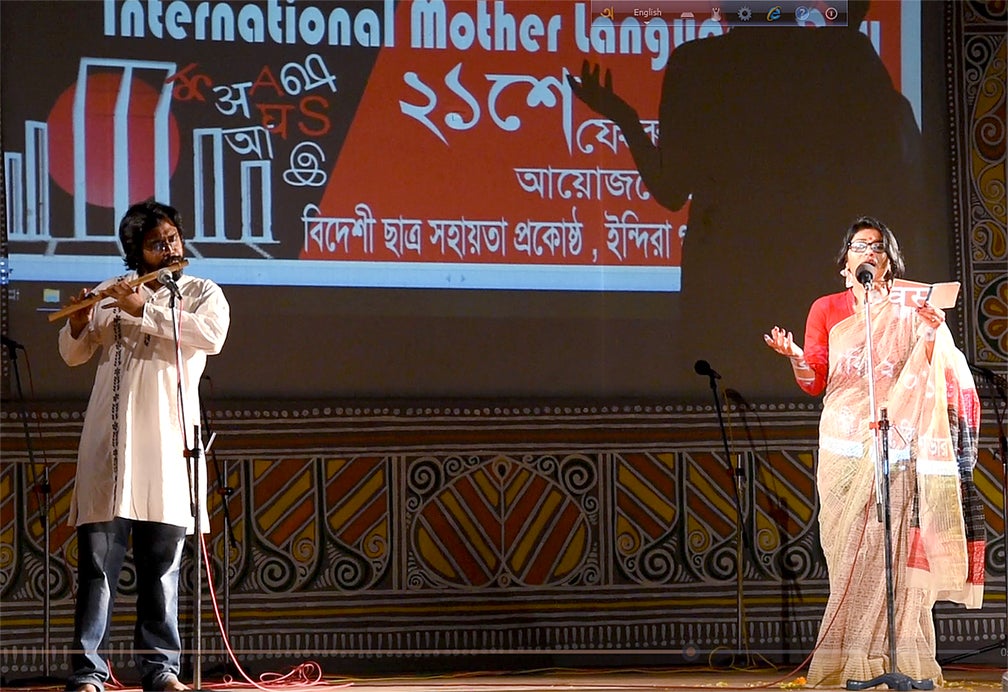

On the contrary, her husband and son turned out to be her biggest supporters. Her husband, understanding her creative side from the beginning, presented Rachana a sketch portrait of herself when he asked her to marry him. Monon, lulled to sleep by the sound of his mother’s lullabies, continued encouraging her singing as he grew up. When the mother and son attended a workshop in Washington D.C., led by legendary Bengali singer Rezwana Choudhury Bannya, Rachana told Rezwana that she was also trying to make her dreams come true.

After years of cultivating her talents and setting aside savings, Rachana was finally accepted as a student at Visva-Bharati University. But before she could leave, another obstacle threatened to hold her back.

As the months until her departure dwindled, Rachana’s visa to travel to India still had not been granted. When she went to the Indian embassy to find out why, the reason was disappointingly familiar.

“[The embassy officer] could not believe I was going to leave my family, leave my computer science job to go to India, just to learn music,” Rachana said.

“So I told him, ‘That’s a problem with your belief. This is my dream.’”

But by the time her visa was finally granted, it was too late. Rachana would have to spend another year filling out application forms, cajoling embassy officials and waiting to see if all of this work was worth it.

This time, it was. In 2016, Rachana finally arrived at Visva-Bharati as a student at the Sangit Bhavana school. For the first time, she was completely free of constraints on her artistic spirit.

“I didn’t have to worry about household stuff. I could lock myself in a room, singing, dancing, painting, writing,” Rahman said.

During difficult periods of homesickness, Rachana found peace standing in the garden of Tagore’s historic home at Santiniketan, listening to the birds singing in the night.

“In the same way you can see the change of the seasons in Kentucky, you can see them [in Santiniketan]” Rachana said.

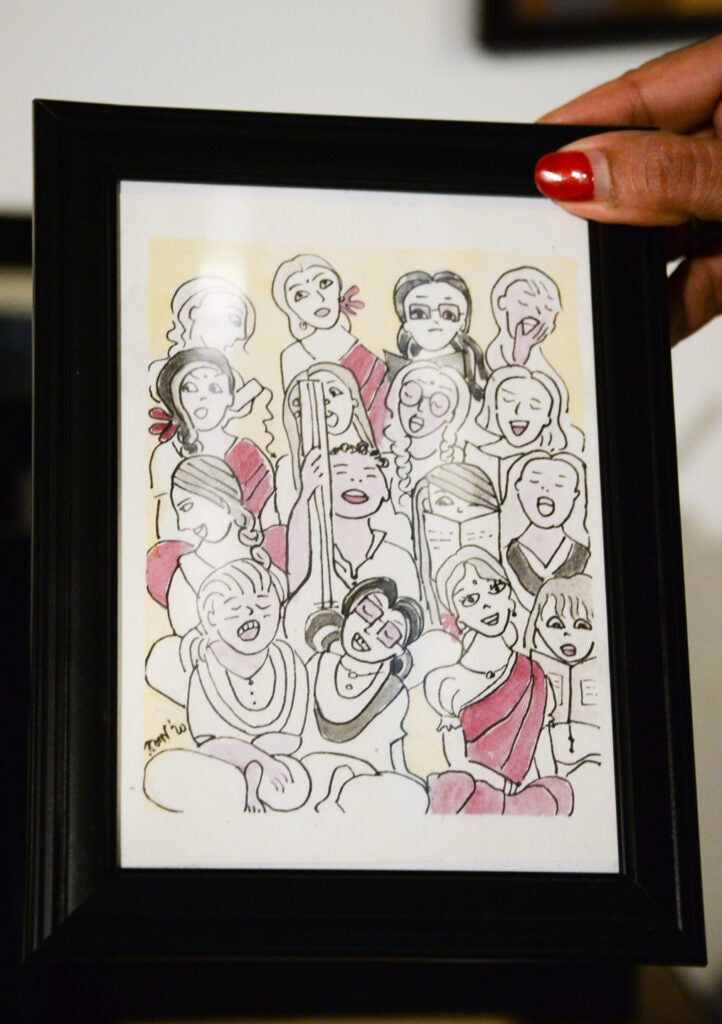

Studying at Visva-Bharati was one of Rachana’s most fruitful times as an artist. In her classes, she learned the dulcet melodies of Rabindra Sangeet, which refers to the vast swath of musical compositions by Tagore. Her minor in Rabindra Nritya allowed her to return to the acting and dancing days of her youth, performing in a variety of dance-dramas. Her classmates encouraged her to begin drawing once again; her sketches from the era show the silhouettes of her peers rendered in joyful pastels, bursting with creativity.

“I think going there was the best decision of my life,” Rachana said.

When she returned back to the United States, an entirely new journey awaited her. For so long, her creative ambitions had been defined by this single, shining dream. What did it mean for her art that she had now achieved it?

For a while after coming back, Rachana felt isolated as an artist. She was unsure if she should continue pursuing music. But on the recommendation of her friends, Rachana began posting videos of herself singing on her YouTube channel “O, where do you come from?”

Her videos caught the attention of Ron Whitehead, former National Beat Poet Laureate and subject of the documentary “Outlaw Poet.” After communicating over social media, Ron and Rachana forged an artistic connection that resulted in her being featured on his poetry album “The Great Blue Heron of Quasar Poetry.”

After this experience with artistic collaboration, Rachana was finally able to put one of her long awaited projects into action. Back at Visva-Bharati, she had thought about one day creating an album of Tagore poems, sung in Bengali and English. Though she worried about whether Western artists would truly appreciate Tagore, she decided that it was time to make this vision a reality.

Rachana’s aforementioned yellow folder began to fill up with translations, compositions and ideas for this innovative, bilingual vision. Along with Ron, former Kentucky Poet Laureate Lee Pennington and vocalist Katrina Harper also came on to the project. As the resident Bengali, it was up to Rachana to make sure that they did Tagore justice.

After over a year of work, “Under the Western Sun: Songs & Poems of Tagore” was released in April 2024. In tracks like “Ye Banks and Braes” and “Poem #103, in One Salutation to Thee,” Rachana’s rich, slightly smoky voice sings in Bengali and Katrina sings the lyrics in English. She described the title as representing her experience making meaning out of Tagore in the context of a different homeland.

“As a Tagore lover, it’s our responsibility to bring Tagore to the world as purely as possible. I think I did that,” Rachana said.

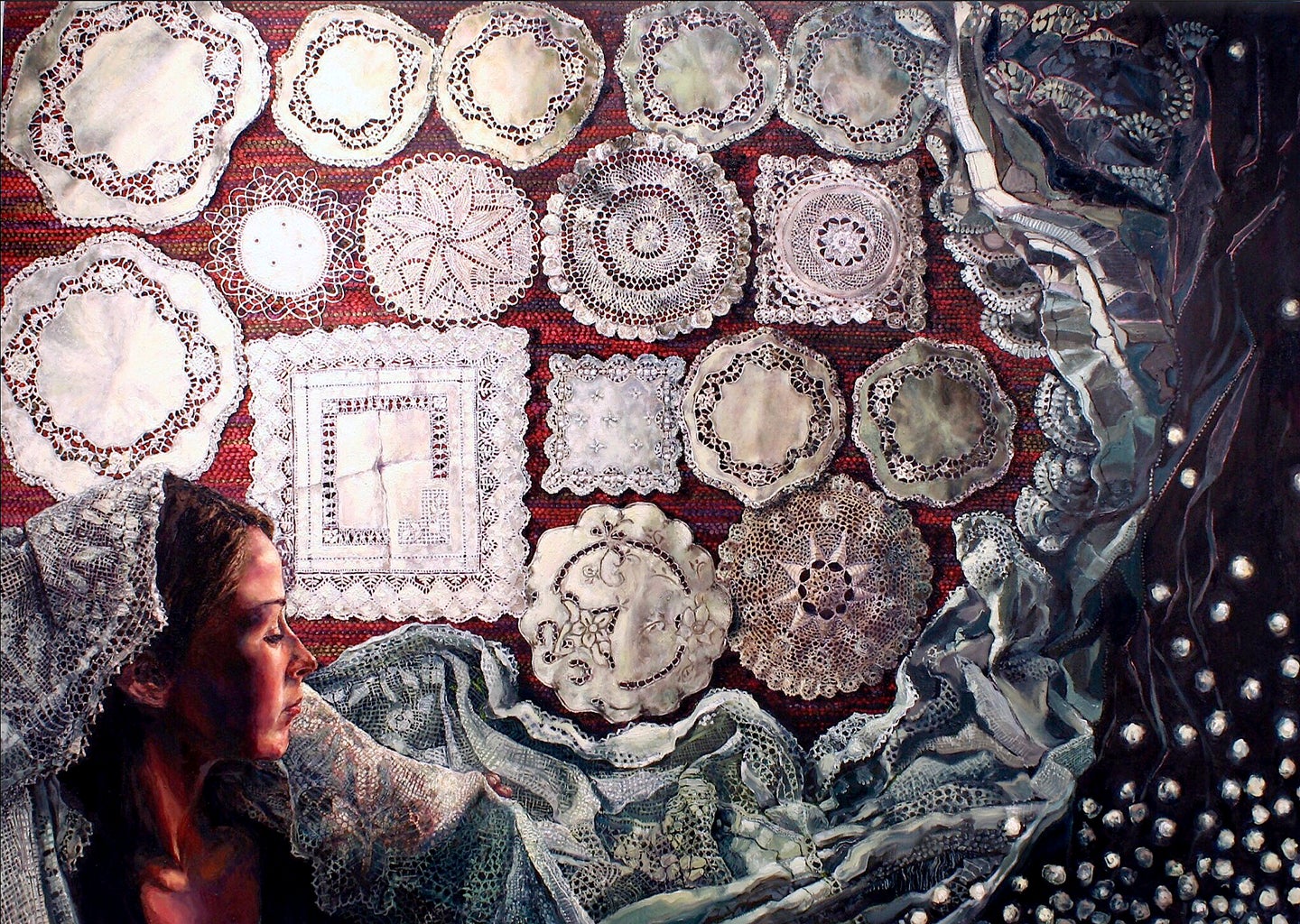

In addition to bringing Tagore into the world, Rachana continued to embrace all aspects of her artistic spirit. Her passion for painting began to flourish, resulting in a makeshift studio in her basement and scores of vibrant, beautiful works celebrating Hindu goddesses, mother-child relationships, and other heartfelt themes.

Soon, the rest of the world began noticing Rachana as well. Her painting “Lady with a Nose Ring” was featured in the Fall 2022 Team Kentucky Gallery at the Capitol. Another painting, “Under the Crabapple Tree,” was chosen by the Louisville Tourism Department to be displayed as a street banner. In 2022, her work debuted in the exhibition “ACCEPTANCE” at the Jane Chancellor Moore Gallery; a dazzling accomplishment for a self-taught painter.

Rachana also continued to make waves as a writer, with her short stories and poems being published in Pegasus, The Kentucky River, Trajectory and Eastern Iowa Review. In 2021, she was selected as one of the four finalists of the Poetry Unites Kentucky essay contest and was featured in a short documentary where she discussed the impact 0f her favorite poem on her life; to no one’s surprise, the poem was “Gitanjali 35” by Rabindranath Tagore.

If she stuck to just one discipline, Rachana believes that she would be able to achieve further recognition for her work. But doing so would deny the multifaceted nature of her own artistic spirit. As she is, she is content to keep realizing her diverse dreams, making her art without worrying about what life will continue to bring her.

“Everytime I wake up, I have a hundred projects in my head. If I can do only one, I’ll be happy,” Rachana said.

To further explore Rachana’s work, follow her Instagram account @rachana_lovesart or email her at myartexists@gmail.com.