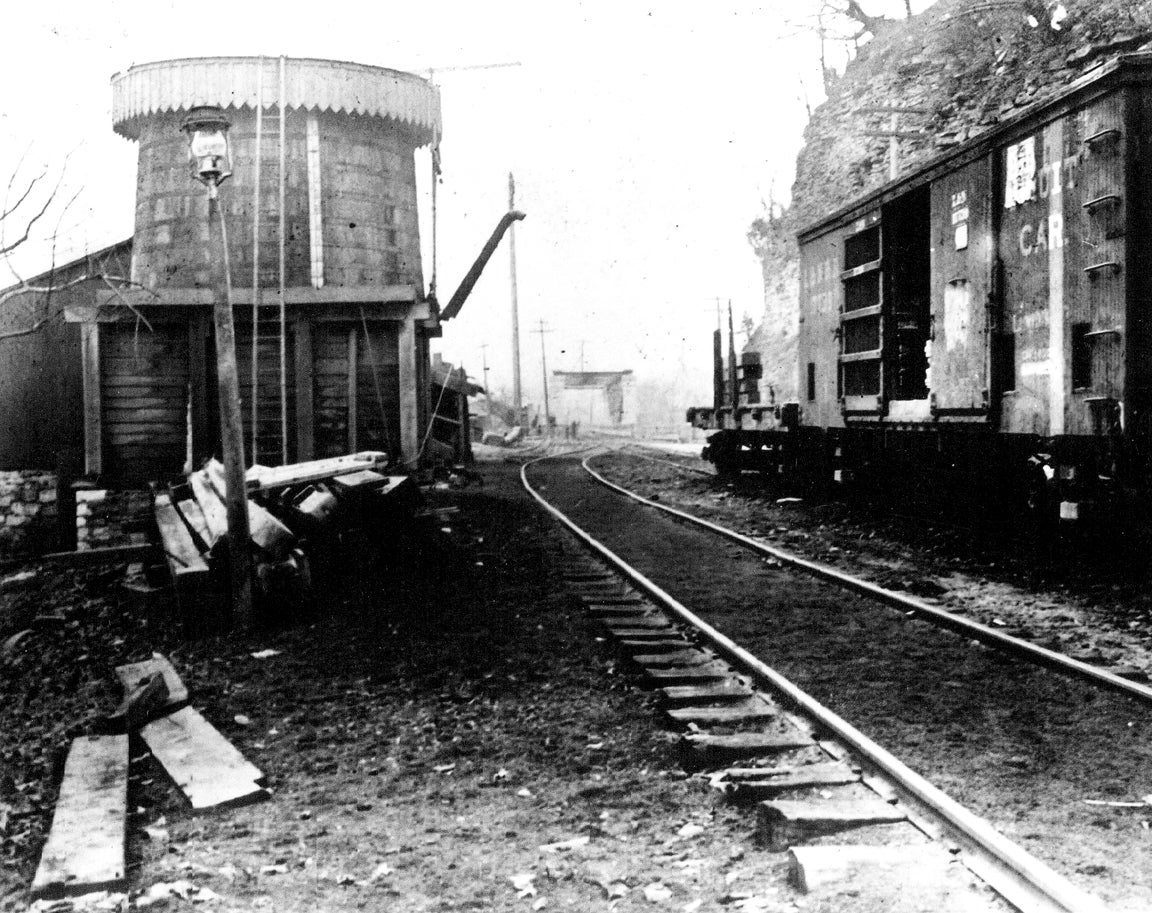

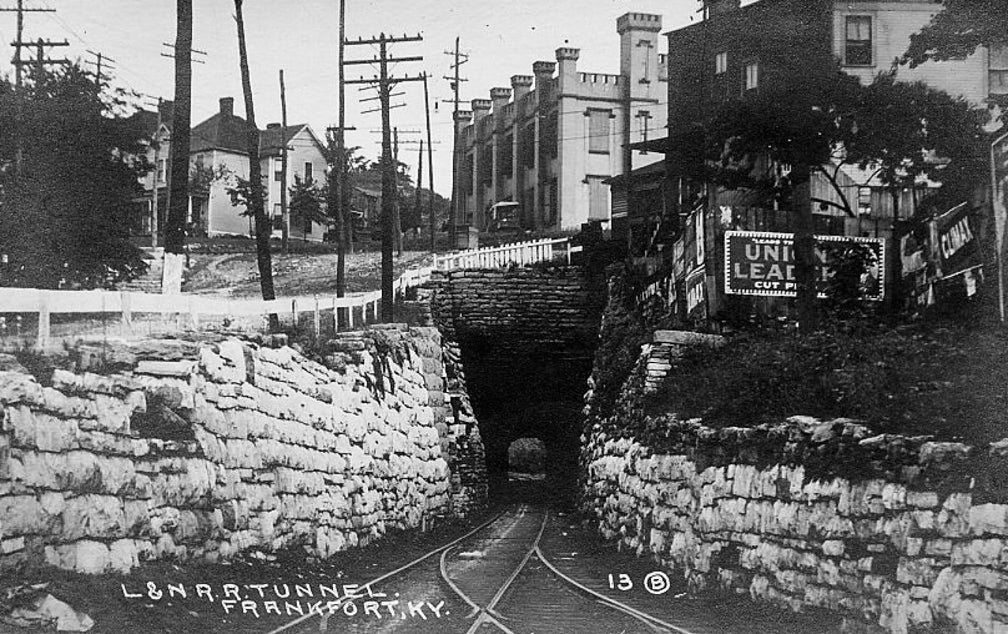

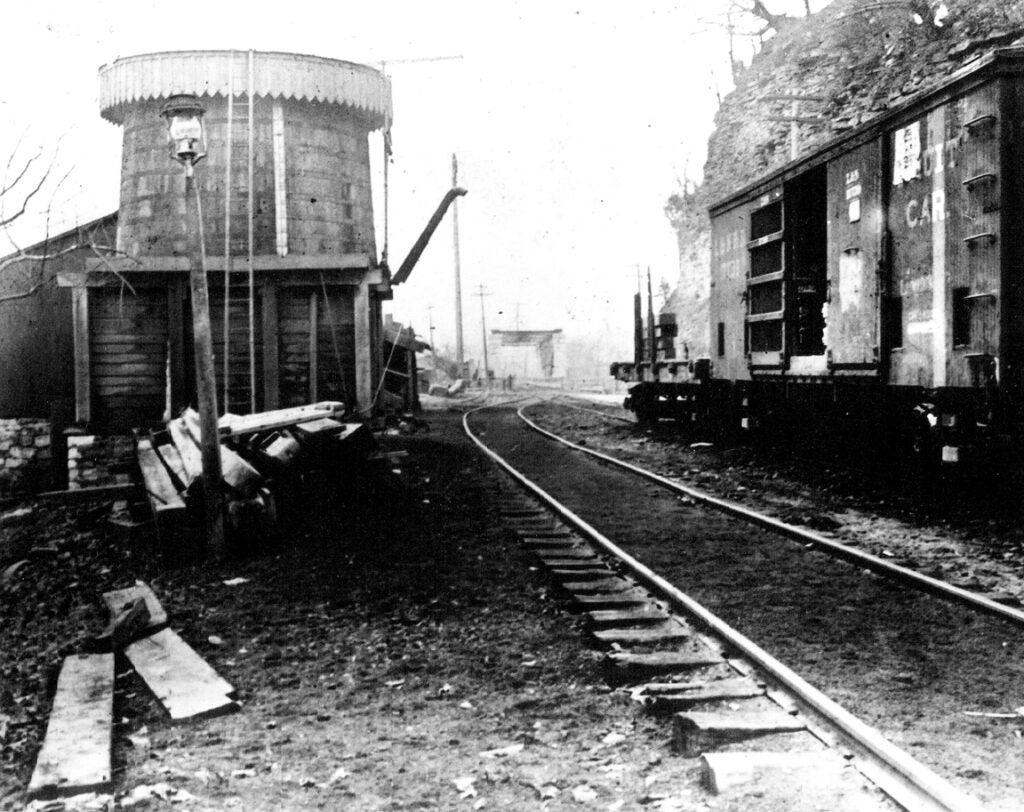

West Frankfort, the area between Buttimer Hill and Bellepoint was, at the start of the 20th century, a thriving industrial based community. There was located the Frankfort Bottling Company, the Old Judge Distillery, the T.J. Congleton & Brothers lumber mill, E.M. Williams Coal & Grain Company, the Louisville & Nashville (L&N) Railroad Yard, and other small industrial establishments. The L&N Railroad Yard contained a locomotive service building, a coal fueling station, an ash removal pit, a water tank, a team track for unloading rail cars and a stockyard.

From 1820 to 1950, trains in the United States moved behind steam powered locomotives. To operate, these steam locomotives needed fuel, wood or coal, and water. The wood or coal fuel heated the water turning it into steam. The expansion and contraction of the steam moved the locomotive’s piston rods that turned the locomotive’s driving wheels.

The locomotive’s fuel and water were carried in a tender located directly behind the locomotive. The fuel was fed into the locomotive’s firebox by the train’s fireman, and the heat thereupon generated in the firebox turned the water in the locomotive’s boiler into steam. Once it had driven the driving wheels’ pistons, the steam was released into the atmosphere via the locomotive stack. This release of steam up the stack drew more oxygen into the firebox to sustain the firebox fire.

From the foregoing, it is apparent that as the locomotive moved down the track pulling its train, it consumed both the fuel and water carried in its tender. Typically, a steam locomotive could travel 100 miles before needing refueling and 50 miles before taking on water. Terrain, however, could cause increased fuel and water consumption. Thus, water tanks were often located some distance from a town to supply needed water in a remote location.

These isolated water tanks were quickly surrounded by a depot, stock pen, general store and a few houses. Once a track side water tank fell into disuse, the surrounding buildings were abandoned and the land was reclaimed by nature.

The climb up and out of the Kentucky River Valley, both east and west from Frankfort, was a consumer of a steam locomotive’s water. Thus, a water tank for refilling a steam locomotive tender’s water tank was located on the north side of Benson Road, just west of Taylor Avenue. Water tanks were also located at Bagdad and Duckers.

In filling a steam locomotive’s tender, the engineer positioned his tender under the water tank’s discharge pipe that would carry the tank’s water to the tender’s holding tank. When the discharge pipe was in a vertical position, a ball within the pipe prevented water from flowing out of the water tank. When water was to be taken on board, the locomotive’s fireman climbed from the locomotive’s cab to the rear of the tender where the tender’s water tank was located.

The tender’s water tank hatch was opened and the fireman grasped a rope to pull the water tank’s discharge pipe downward, displacing the ball and allowing the water tank’s water to flow into the locomotive tender’s holding tank. To start the lowering of the water tank’s discharge pipe, the fireman had to give the rope a jerk before applying a steady pull to the rope. Thus, an isolated town or community situated around a railroad water tank was known as a “Jerkwater Town” or “Jerkwater Community.” West Frankfort, in railroad lingo, was a jerkwater community.

Circa 1958, with the removal of the L&N water tank, coaling tower, and railyard from West Frankfort due to the arrival of diesel locomotives, another American jerkwater community faded into the sunset. There are very little physical remnants on the ground today to show that people once lived and worked in West Frankfort, a proud jerkwater community.

The Capital City Museum is always interested in artifacts or photos of Frankfort and Franklin County to add to their archives.