By Charlie Baglan,

When we see it, we stop. For a minute, we stare. And although we’ve seen it too often to count, it commands our full attention. The full moon.

In Kentucky, just a couple of hours south of Frankfort, the moon does more than inspire love songs. It leaves latenight travelers mesmerized for hours. I know, it still happens to me. I photograph it. Not the moon, but something it creates — the Cumberland Falls moonbow.

Each year, thousands visit Cumberland Falls State Resort Park near Corbin to see the “Niagara of the South,” but few plan a day when they can stay to see the moonbow. Those who do hardly believe their eyes. It’s not a myth. Naturally, they reach for their phone to snap a picture, but photographing the moonbow is tricky. If you follow a few steps with the proper equipment, this natural rainbow at night can be suitable for framing.

As a rainbow is formed by sunlight, the moonbow is moonlight refracted in the mist of the falls. Our human eyes can’t see the colors. So, it appears as a ghastly white arch at the base of the falls and extending down river.

Cumberland Falls is the only place a moonbow is seen in the U.S. with year ‘round monthly predictability. Light pollution from street lamps at other picturesque falls, such as Niagara, obliterates any bow that would appear. Kentucky has cornered the market on this phenomenon and people travel from around the world to witness it.

What’s needed are a full moon and a clear night, but it is also viewable a couple of nights on either side of peak illumination. Because the moon follows an elliptical orbit around Earth, viewing times vary from night to night. With a clear sky, there is usually a two-hour viewing window. Check with the park desk for optimal viewing times or find them online at parks.ky.gov.

The first overlook just down from the gift shop is the only place the moonbow is visible. It’s not seen downstream, from area trails, from a kayak on the river nor from the opposite bank. Your eyes, the mist and the moonlight must all align. While at the overlook, do others a favor by keeping lights off. Smartphone and tablet screens, camera flashes, flashlights, camp lanterns and any other stray light ruin the view for everyone — as well as the photo someone may be taking.

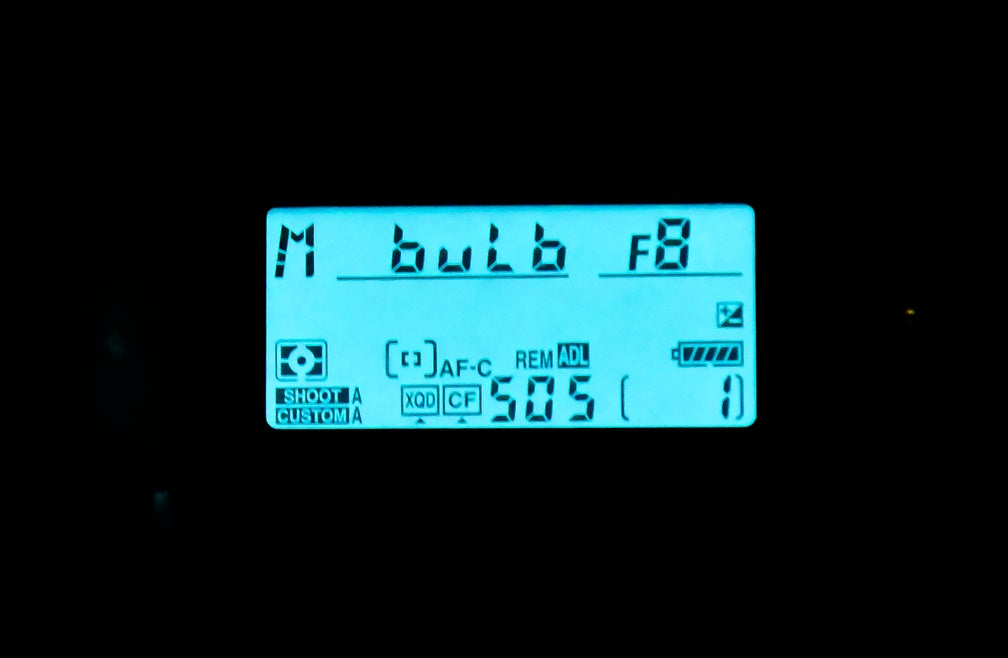

If you want to try your hand as photographing the moonbow, put your cell phone camera away. You’ll need a camera that allows manual settings such as a digital single lens reflex camera (DSLR). These are the higher-end models with interchangeable lenses. Some of the newer point-and-shoot models may suffice if they provide long shutter speeds and high sensitivity settings. Determine its capabilities at home before you leave. Because the exposure is prolonged — perhaps 45 seconds — your camera must be on a sturdy tripod to avoid blur.

Cats and owls see well at night, but not people. We can’t finely discern differences of the moon’s radiance from night to night, but cameras do. Hence, exposure settings will vary with the clarity of the sky, the amount of mist generated in the plunge basin of the falls and fullness of the moon. Therefore, we must rely on some trial and error with our settings. A good place to start is:

- ISO: 400

- Aperture: f-8 to enhance focal sharpness.

- Shutter speed: 45 seconds — timed manually using the Bulb setting in manual mode.

- Focal length: Infinity

- Format: RAW or jpeg large/fine.

- No flash

- Tripod

Many newer DSLRs feature a high-sensitivity image sensor that allows you to reduce exposure time by half or more depending on the setting selected. It’s not as technical as it sounds. Unless your camera has options for these lengthy shutter speeds, the likelihood is that you will need to hold the shutter open manually (with a cable release) as you watch a timer.

Anything that moves will blur. The flowing water will appear as cotton, rustling leaves on trees will soften, but they are offset by the tack-sharp boulders on the hillside and the vivid bands within the bow.

Don’t be in a hurry. The processing time to render the photo is generally equal to the shutter speed. Thus, a 45-second exposure equals an additional 45 seconds to show on your screen. In other words, a full minute and a half from start to finish. So, when the camera doesn’t immediately reveal the shot, nothing’s wrong. Don’t turn the camera off while it’s processing. Be patient.

Adjust from there for under or overexposure. Typically, shortening or lengthening the shutter speed in increments of a few seconds will land you on a properly exposed photo.

Once you do, you will be stunned. While a white arch appears before you in the night air, your camera reveals the surprising blue, yellow and red rainbow colors, shadows in the rocks and a blue sky. In addition, it is a nice pat on the back from other folks gathered as they ooooh and aaaaah over your photos in similar disbelief. Should you see a postcard of the moonbow that looks like a daytime rainbow, now you know why.

Once home, you might try minor tweaks in your photo software for cropping, color and contrast. But as-shot, the image is very real and very much a Kentucky scene that so few have ever seen. There is no better way to spend a night along the Cumberland River far from home. Thank goodness for the park campground, cozy cabins and DuPont Lodge because it will be late when you finish — at which point, you’ll find yourself secretly making plans to bring friends and come again.

Charlie Baglan is a Frankfort resident and lifelong Kentucky photographer whose moonbow tips have appeared on KET, FOX 17 News in Nashville, Tennessee, Kentucky Afield Radio and Kentucky parks and tourism websites.