“Humanize: A Guide to Designing Our Cities” by Thomas Heatherwick

Critics say, “Our world is losing its humanity!” World renown British designer, Thomas Heatherwick, says, “We must humanize our buildings.” He points out that politicians care more for their re-election over the people that voted for them. And this attitude creates cities designed for business instead of for people. With the newly implemented “work from home” option, many of our corporate company offices are now looking for less space at a more affordable rate. Thus, leaving cities with a surplus of empty buildings.

Heatherwick first looks at what makes human places. He suggests that humans are drawn to complexity and repetition. He gives the example of a Greek temple with the repetition of columns or the timbered beams in the ceiling of a Tudor house.

Humans also like complexity such as the styles of both the Gothic and Art Nouveau. The Spanish architect, Gaudi, displays a complexity that is astonishing. He uses wood, unpolished stone and brick, but will contrast that with an iron balcony that twists as it rises. Millions of people visit Spain to stand and stare at Gaudi’s creations. Gaudi’s buildings are on numerous “bucket life lists.”

Frank Lloyd Wright experimented with complexity and repetition in his designs. Frankfort’s “Jesse Zeigler House” from 1910 has repetitive horizontal lines and complex art glass windows.

Heatherwick includes photos of buildings from a dozen of different countries that he labels boring in their disconnect to the elements of humanity. From the USA, to Russia, Argentina and to Kenya, there are scores of buildings that lack the “human” requirements. Heatherwick labels these buildings “boring.” People find them disinteresting, avoid them, and have no desire to live in them or preserve them.

Frankfort is fortunate in that we have much of our early buildings intact. Visitors frequently comment that our town is so charming. Lexington’s downtown was not as fortunate and embraced the wrecking ball destroying much of its history. Louisville has discovered that there is a tourist market in “Whiskey Row,” which features the cast iron store fronts from the late 1800s. Though the Market Street buildings are similar in size, and set-back, they each have distinct window designs and a variety of columns.

Yes, boring buildings may be more profitable in the short term, and a financial win for developers. And clearly, the developer does not see the public as the ultimate consumer. The result is a public that disregards these buildings, and has no interest in preserving them. “Team Money” wins over “Team Public.”

A balance of complexity and repetition creates a building that people want to see because it is not boring. A building that is interesting from many different angles is a bonus. Think of the Serafini building with its door on the corner, and different window designs on the Broadway front from the windows on the Saint Clair front.

Read Heatherwick’s book and take note the next time you visit our downtown. Decide for yourself which buildings are boring and which have more “humanized” elements.

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“Let Us Descend” by Jesmyn Ward

Jesmyn Ward, a two-time National Book Award winner was raised in Pass Christian, Mississippi, and has been a major, brilliant voice of recent southern literature.

Ward’s fourth novel, “Let Us Descend” is set in the hell of slavery before the Civil War. Annis, a teenaged enslaved girl, is raised on a rice plantation in the Carolinas with her half-sister, the daughter of the plantation owner. Annis gained more education than other slaves by listening to her sister read her books out loud.

Annis’s mother comes from a line of African warriors and she is determined that her daughter will know how to defend herself. Before Annis’s training is complete, her mother is sold at the slave market and Annis is on her own. She realizes that the last book her sister read, “Dante’s Inferno,” is beginning to be reflected in her own life.

Annis, too, is sold to a slave marketer with others from the plantation, and forced to walk to a larger market in New Orleans. The travel was perilous with many hazards. Ward spends chapter after chapter describing the day to day ordeals of the captives, passing through treacherous, horrific, swampy territory with barely any provisions provided.

The tension building in the novel is finally released when Annis is sold to a sugar plantation owner. Life is better than the tortuous journey even though the smallest infraction could put one in the “hole” for days on end without food or water.

Ward tells a tale of rebirth and redemption using the magical realism of Annis’s female ancestors that she calls upon when overwhelmed with cruelty and injustice.

Not only does Ward completely describe the hardships that enslaved people endured but she does so with a poetic voice that does not invalidate the story but does help the reader continue reading Annis’s unforgettable, tragic narrative.

Pam Miller, critic with the Minneapolis Star Tribune, said “As long as America has novelists such as Jesmyn Ward, it will not lose its soul.”

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“The Invisible Hour” by Alice Hoffman

Alice Hoffman gives us another magical story in “The Invisible Hour.” It’s a tale of loss, love and freedom.

Mia was born into a cult in western Massachusetts where books, family and individualism were banned and punished. Mia wished to run away with her mother, but tragically that dream was taken away when a terrible accident left Mia alone. Secretly, before the accident, her mother introduced Mia to the wonder of books and taught her how to visit the library unseen by Joel — the cult leader and her father.

During her secret visits, she happened upon a book with a strange handwritten inscription: “To Mia.” Why did the book have her name in it? Why did the story feel so familiar? Just when she thought all hope was lost, this book made her believe in a different future and gave her the courage to run.

In part two, Mia time travels and has a love affair with the author of the book, Nathanial Hawthorne. Joel relentlessly chases her but her conviction to the future she should have had with her mother and the future she chooses to have with Nathaniel keep her fighting for her happily ever after.

— Review by Heather Avila, Paul Sawyier Public Library

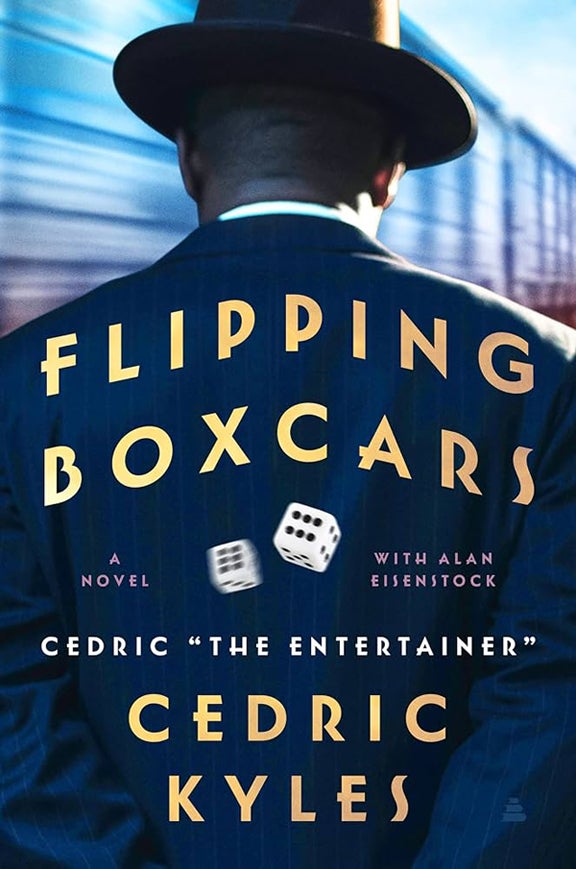

“Flipping Boxcars” by Cedric “The Entertainer” Kyles

Babe. Larger than life, con man, rogue, gambler, fixer, legend. 1948, Caruthersville, Missouri, Babe Boyce has his hand in numerous enterprises — bootlegging whiskey, running craps games, operating a diner with his wife, Rosie. He’s part entrepreneur, part flim flam man. Babe has his sights on a rundown mansion he plans on remodeling into an entertainment complex — bar, restaurant, hotel — a black-owned business catering to the people on his side of town.

To finance this, Babe makes a deal with a Chicago mobster to buy and resell a boxcar of whiskey, 3,000 cases for $54,000. In order to pay for the whiskey, Babe sets up a crap game inviting heavy-betting gamblers from across the country and Babe never loses.

All the characters in this book were based on real people. Babe and his wife were Cedric’s grandparents, their daughter, Rosetta, was his mother. Sheriff Carl Holt was Babe’s best friend from a teenager. He met his bodyguard, Karl, on D-Day, storming Normandy Beach. This is one of those stories that drew me in from the beginning — I felt like I was right there with Babe as he faced off with KKK members, suffering the heat of July nights, feeling the sweat rolling down his back as he threw the dice on the biggest gamble of his life. Cedric certainly entertained me and I hope he continues writing Babe’s story.

— Review by Karyn Collins, Paul Sawyier Public Library