When the Civil War started in 1860, Kentucky was a slave owning state. When the Civil War ended in 1865, Kentucky was still a slave owning state. It was legal in 1865 to own slaves in Kentucky as President Lincoln’s 1862 Emancipation Proclamation — setting slaves free — only applied to slaves owned in areas in rebellion against the United States.

Kentucky in 1862 was a loyal state and thus not affected by the Emancipation Proclamation. Slavery in Kentucky only ended on Dec. 6, 1865, when the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution — which outlawed slavery — went into effect.

Between 1861 and 1865, Kentucky had been a battleground. The state suffered damage from actions by Confederate and Union armies and raids by Confederate cavalry and guerrilla units. The years 1866 through 1875 were not much better for Kentucky. During this period, the state was in armed turmoil as the citizens of Kentucky sought to re-establish the prewar economic prosperity and political influence it had enjoyed before the Civil War. This period saw whites attacking whites and whites attacking African Americans. The result was that many of Kentucky’s African Americans migrated north of the Ohio River or moved to Louisville.

During the years of the Civil War, the State of Kansas had also suffered economic disruptions from raids by Confederate units. Kansas in 1865, however, differed from Kentucky in that it was not and had not been a slave owning state. Also, during the course of the Civil War, the state had armed its African American citizens and deployed them in combat next to white Kansas regiments. While a number of African American regiments were raised in Kentucky in 1864 and 1865, they were raised by the Federal Government — United States Colored Troops (USCT), not by the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Also, the USCT regiments raised in Kentucky did not serve alongside any Kentucky raised units fighting for the federal government.

During the years after 1865, African Americans in Kentucky had only to look around their homes and neighborhoods to see that despite the promises of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, their lot was not improving. Reports however filtered into Kentucky’s African American community that a life free of white racism could be found on the Kansas frontier. That in Kansas — under the provisions of the 1862 Homestead Act — any African American man could lay claim to 160 acres of federal land and grow an abundance of crops to support a family.

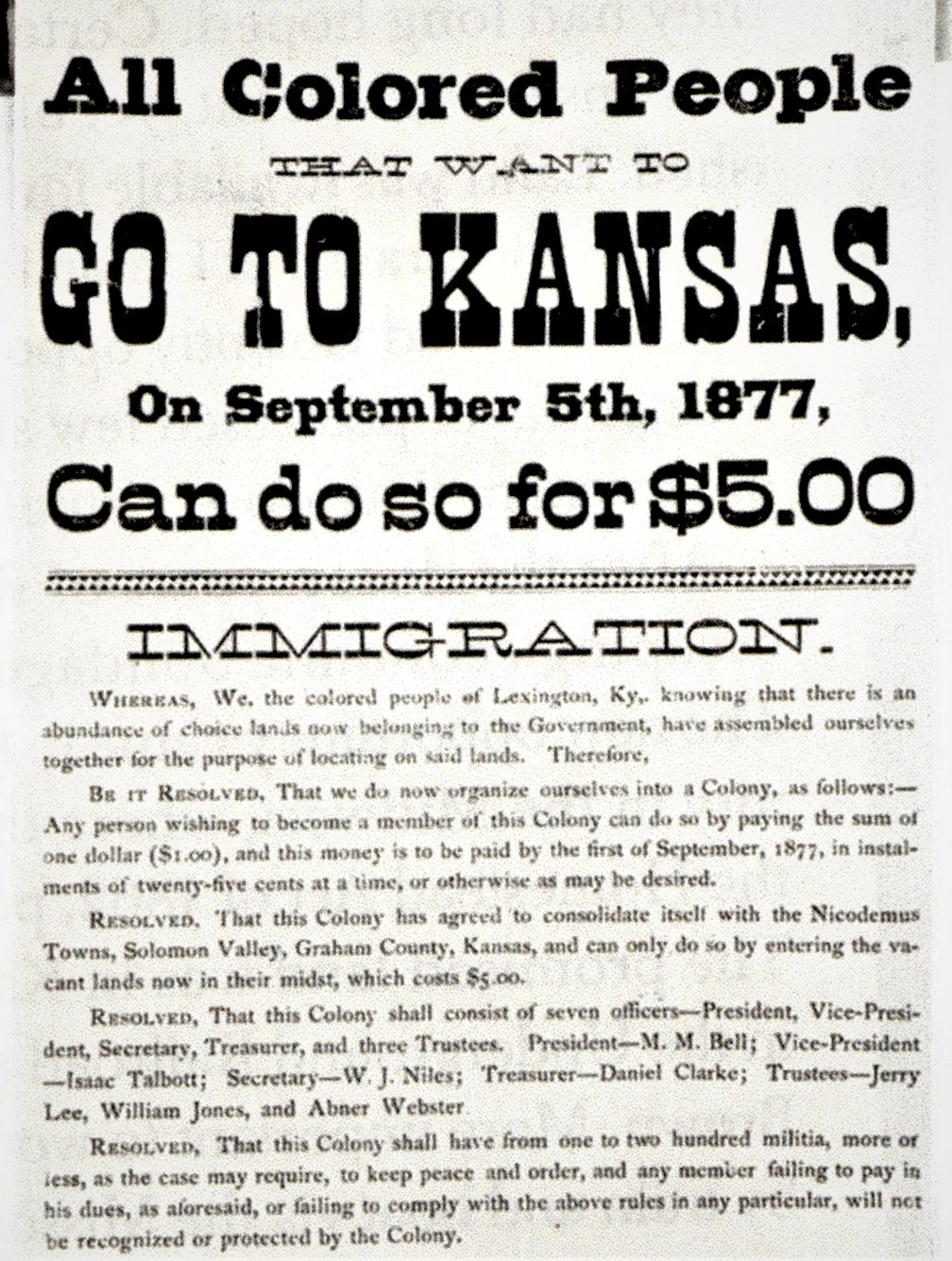

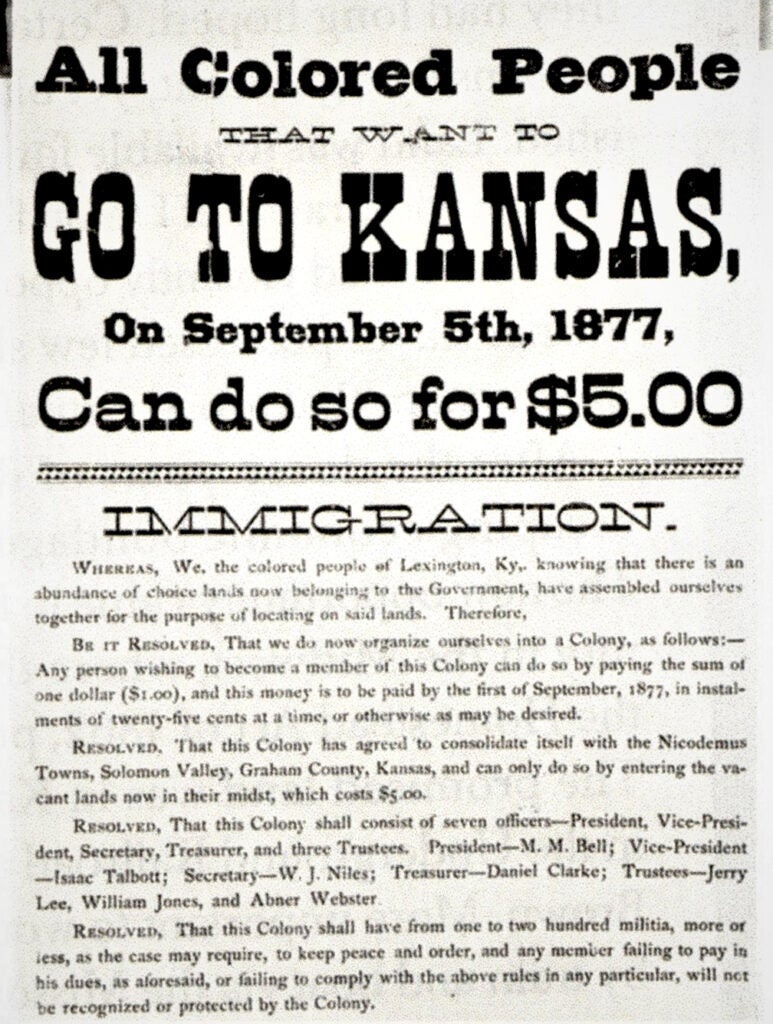

The cost of travel from Central Kentucky to Kansas, however, put the journey west to homestead out of reach of the members of the African American community. However, in 1877 a white land speculator, W.R. Hill, journeyed to Central Kentucky from Nicodemus, Kansas. He visited various African American churches in Bourbon, Fayette, Scott, Woodford and Franklin counties praising the richness of Kansas soil and the ability of a head of a household to obtain 160 acres of this farm land for himself under the provisions of the Homestead Act. While Hill’s description of Nicodemus did not quite say its streets were paved in gold, he did make it sound like they were paved in silver.

Hill quoted a $5 per person train fare from Lexington and Frankfort to Nicodemus for those African Americans who wished to become landowners. Once at Nicodemus the new settler had to pay a $1 membership fee for a lot within the city and $5 for his homestead land. While today this does not sound like a lot of money, $5 in 1877 was, for most Kentucky African Americans, more money than they saw in a year.

However, on Sept. 17, 1877, some 350 African American men, women and children having raised the necessary cash boarded at various stations in Fayette, Scott and Franklin counties a Louisville & Nashville Railroad train heading for Louisville. From Louisville, these settlers traveled by train north to Seymour, Indiana, and then west for St. Louis, Missouri, and Ellis, Kansas. From Ellis, it was a wagon journey of 35 miles over open prairie before Nicodemus was reached. The settlers upon arriving at Nicodemus quickly realized that Central Kansas was nothing like Central Kentucky. Instead of a landscape covered in lush bluegrass cut by numerous small streams, they found a land of brown grass devoid of bubbling streams. As for Nicodemus, not only were the streets not paved in sliver and they were not lined with wood framed homes. Instead of eastern style homes, the citizens of Nicodemus lived in dugouts or sod homes next to a rutted dirt street.

While the landscape that greeted these African Americans from Central Kentucky fell well short of what they expected to find, they set out with a will to create their own community. Over the next few years, 150 more African Americans from Central Kentucky joined the original settlers. Soon, the streets of Nicodemus were lined with wooden framed houses along with stores, a school and church. The town and its citizen thrived until 1930 when drought, coupled with the Great Depression destroyed the viability of the area’s economy. Most of Nicodemus’ citizens headed for California, and the town ceased to function as a community as its population fell to 20. However, in 1996, the surviving structures within the city of Nicodemus were designated by Congress as a National Historic Site and annually, during the last weekend in July, a homecoming celebration is held.

Unfortunately, the Capital City Museum has no information on the African Americans from Franklin County who journeyed west to Nicodemus, Kansas. Any information concerning the migration would be welcomed.