By Chris Easterly,

Morning sunlight spilled through a wall of windows, bathing the common room at the King’s Daughters Apartments in an optimistic glow. Resident Pat Price separated holiday cards at a table.

“We have so many Christmas cards donated each year, at least five or six hundred,” she said. “It’s a big job.”

Price and fellow resident Linda Updike were sorting the cards to be sold for two dollars apiece at the Frankfort Senior Activity Center. Their other projects include collecting hats, scarves and gloves for Second Street School children, and assembling packs of toiletries for the nearby men’s shelter.

“We have had so many things done for us down here,” Price said, noting the local churches that serve hot lunches on Saturdays and bring fresh fruits and vegetables to the apartment complex. “These residents here have worked so hard to pay back.”

Price and her friends are continuing a tradition of service that goes back more than a century to the founding of the place they call home.

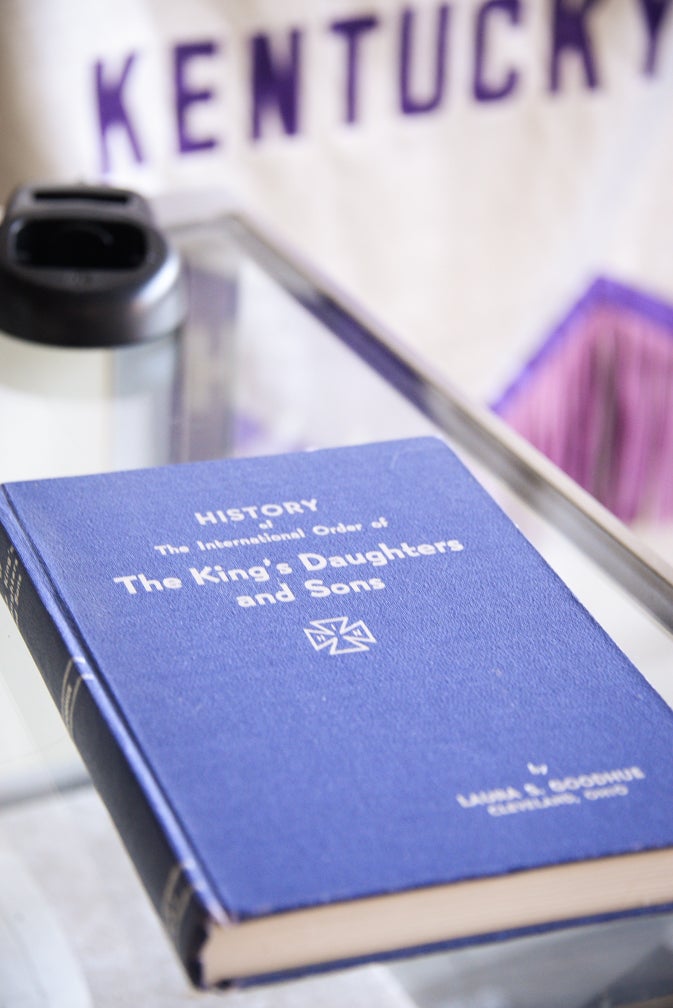

The Order of the King’s Daughters was started in January 1886 in New York City by 10 women interested in helping the poor. The organization began as, and remains, an interdenominational Christian service organization.

Within one year, King’s Daughters grew so fast that a public meeting was held at the New York City YMCA because so many people wanted to learn how to get involved. In 1887, the organization opened to men and became the King’s Daughters and Sons, dedicated to various charitable projects serving the needy and disadvantaged.

The movement caught fire and spread to Canada, Ohio, and soon, Kentucky. Fanny Duncan, along with her sister and a friend, formed the first Kentucky circle in Louisville. They opened a “home for the incurables,” a residence for people suffering from physical and mental illnesses.

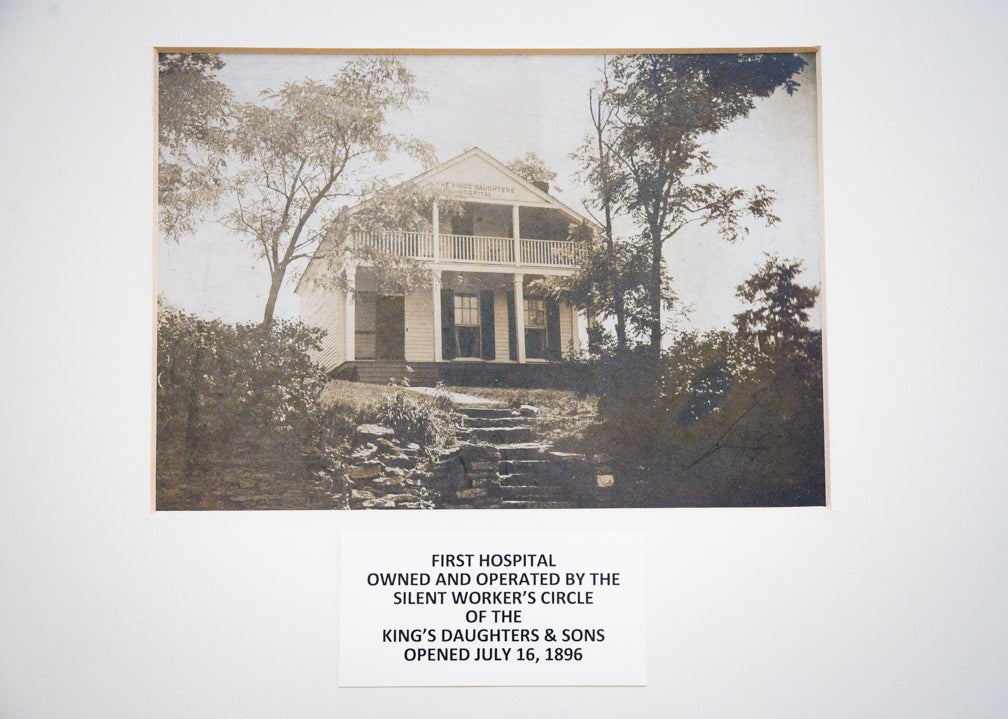

Eight years later, in October 1894, 14 women met and formed the Silent Workers Circle of the King’s Daughters and Sons in Frankfort. Their mission was ambitious — to create the capital city’s first hospital.

Frankfort resident Jerry Brislan offered a dilapidated house on East Main Street at no charge for the first year. The volunteer women scrubbed floors, painted and restored the structure. By 1896, the building known as “the little house behind the lilac bushes” was a medical facility that accommodated seven patients. Women provided biscuits and ham to the sick, and hired their first nurse, Jennie L. Bell, who worked without pay.

The operation expanded and moved to a nearby brick building, adding a new wing. By 1920, 35 beds were available. Rooms cost $15-20 per week and were open to anyone, with the primary focus always on charity patients.

From the beginning, the group’s pledge was “not to be ministered unto, but to minister,” said Joy Feist, current leader of the Frankfort Silent Workers Circle.

The hospital continued to outgrow its capacity to serve, and in 1935, two Frankfort families offered their estates for the establishment of a larger hospital. An estate on Berry Hill was considered too remote at the time, so the King’s Daughters accepted a building at the corner of Third and Steele streets, donated by Judge Russell W. McRery. Three years later, the new facility opened with 75 beds.

In 1938, King’s Daughters was the only hospital in the nation affiliated with four nursing schools. Its food was so delicious that community members started coming just for the meals.

“The cafeteria always had long lines of people waiting to eat, especially on Sundays,” Feist said.

Over the next four decades, the downtown hospital served Frankfort residents. In 1974, the facility closed. The Silent Workers Circle gave the hospital’s certificate of need to Hospital Corporation of America, which established a new, much larger facility, today’s Frankfort Regional Medical Center. A Silent Workers Circle director still serves on FRMC’s board of directors.

After closing the old hospital, the circle had to decide what to do with the building at Third and Steele. They obtained a HUD loan and, in 1981, converted it into a senior citizen’s apartment complex with 81 one-bedroom units.

“This all grew into what we now have,” Feist said of the building that still stands in the heart of downtown.

The Silent Workers Circle owns, maintains and manages the King’s Daughters Apartments, taking a personal interest in its tenants. A board of managers meets on a monthly basis. The circle also supports other charitable endeavors, such as contributing to resource centers at Frankfort schools and ringing bells for the Salvation Army during the holidays. But its primary mission remains serving the historic building’s residents.

“I love it,” said Feist. “We are committed to serving the Lord and we see this as our way of providing service. It’s an attractive, comfortable, safe environment for people to live on an affordable basis. We stick to our mission and continue to look forward, assess and improve and provide this wonderful facility.”

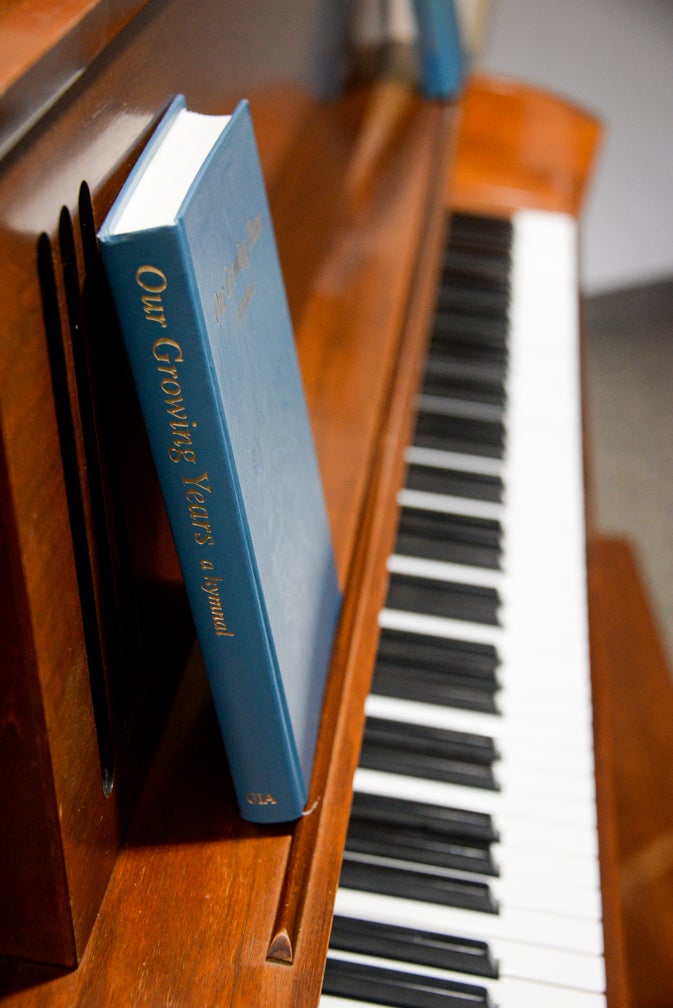

Tenants pay rent and have the option to purchase a weekly meal plan. The staff develops a calendar of activities that’s posted in the lobby for residents. Activities include live music, dance performances and parties. Feist said there is almost always a waiting list to rent the apartments.

One morning in November, several residents lounged in the lobby, chatting as they waited for the cafeteria to open for lunch. Gwynn Brophy was born at the hospital in 1948 and lives there now. Bobbi Thompson, of Massachusetts, has lived there for three years. “I like it,” she smiled. “Everybody’s nice and friendly. We help each other.”

“There’s a lot of activities. You’re around people, you’re not alone,” said Loretta Warner, who grew up in Brooklyn, New York. “I like gambling,” she added. The community’s bingo game is one of her favorite events.

“This is a wonderful place to live,” said Nancy Bogardus, originally from Virginia. “People are helpful and friendly and care about each other, and that means a lot.”

The only thing they all seem to complain about is the recent closing of the Pic-Pac grocery store behind the building.

Meanwhile, back in the common room, Pat Price and Linda Updike continued sorting through Christmas cards to stuff in envelopes. “They don’t know what we do here,” said Price, who moved to Frankfort from North Carolina decades ago. “We’re a family. We are paying back.”

Wherever they came from — Kentucky, New York, Virginia, Missouri, Puerto Rico — most of the King’s Daughters Apartments residents seem to agree on one thing — when they moved here, they found home.