By Bryan Reynolds

As the lights come on, one at a time, in the Kentucky Historical Society’s artifact storage room, row after row of objects covered in tarps and artifacts stored in wooden boxes and filing cabinets are revealed.

“We call that the ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ moment,” said Sara Elliot, Director of Historical Resources.

The Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History is a treasure trove of historical artifacts telling the colorful history of the state.

What’s available to the public, the artifacts on display in The Kentucky Journey and the Hall of Governors, is only a fraction of what the museum stores. The Kentucky Historical Society has existed since the 1830s and has been collecting artifacts since the early part of the 20th century, Elliot said. The KHS headquarters used to be located at the old state capitol and later gained access to the old state capitol annex too, she said.

The Clark Center was built in 1999 because the old location had no temperature and humidity control for the storage.

“It’s very important to maintain the condition of the artifacts, both archival and artifacts,” Elliot said. “A steady temperature and humidity keep the artifacts from degrading.”

The majority of artifacts are donated to the KHS. A collections committee meets twice a month to review whether to accept or reject possible donations. The committee is made up of curators, curatorial staff, education staff, library staff, folklorists and exhibits staff. In order to be accepted into the museum’s collection the artifacts must have a Kentucky connection and tell one or more good state stories, Elliot said. Artifacts also have to be in good condition that can be maintained to be considered for acceptance as well, she said

Once the committee accepts an artifact, a deed of gift is sent to the donor, transferring ownership of the artifact to the museum, she said. After an artifact is approved and ownership is transferred to the center, it is taken to the Conservation Lab where it’s cleaned, if need be, and cataloged. The lab is a room full of stainless steel cupboards and drawers, with a stainless steel table in the middle of the room.

“Cataloging involves measuring it, describing it and doing a condition report,” Elliot said. “Everything we have is photographed and put up online.”

On a November day, Curator Bill Bright was cataloging a Vietnam era uniform and belongings donated by a Vietnam veteran, a sergeant, from Murray.

“He brought the collection in, to do the temporary custody, so we sat around this table with everything out and he explained each piece to me and what the value to him for each piece was,” Bright said. “That’s the important thing, is to remember the story of people who populate this state and define themselves as Kentuckians.”

Bright said he would like to get the veteran back to the center to record an oral history piece, which would be stored in the archives so future curators could access the recording and learn the veteran’s story.

Bright said the museum also received a donation from the family of Marcus Raymond Davis, a sergeant from Harlan County who also served and died in the Vietnam War.

“The two of them (collections) together gives us a broader perspective of what was happening around the state,” Bright said.

The irony of the Conservation Lab is KHS doesn’t do conservation work – cleaning or fixing artifacts — itself. It pays specialty companies to do it, Elliot said.

The storage is separated into two parts — archival and artifact storage. Artifact storage is where KHS keeps everything donated that was physically used throughout history. Archival storage is where documents, rare books, music, photographs and glass negatives are kept.

Further, artifact storage is separated into four different storage areas; main storage, textile storage, painting storage and “the arsenal.” Main storage houses vehicles, heavy artillery, a telephone operator switchboard and Old Kaiser, a still used before the Civil War, Elliot said.

“After the Civil War, the owner sold it to a guy named Uncle Tip Carnes,” Elliot said. “Uncle Tip used it for illegal whiskey making. He used it for about 40 years. He had people who would warn him when the revenuers were coming so he would hide it. He would hide it in the loft of a barn. It’s been hidden under hay bales, and it’s been hidden up in a tree.”

Elliot said Uncle Tip protected Old Kaiser for 40 years until it was stolen by two men, who ended up being arrested with it, in the 1930s. Someone donated the still to KHS in 1949, she said.

Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History also has a collection of 107 original Paul Sawyier prints in the painting storage room. Sawyier did a series of paintings with two lines from a poem titled “The Two Villages,” and it’s part of the collection in storage. The poem was published in the Frankfort newspaper in the late 1880s or 1890s, Elliot said.

“My theory is that Sawyier read the poem and went ‘Wow that sounds like Frankfort,’” she said. “So, he painted these scenes and put two lines of the poem, and the scene is supposed to illustrate the stanza.”

Meanwhile, archival storage is located in a chilled room, with fans creating constant circulation to ensure the humidity stays at the correct level and so the books and documents are not ruined, Elliot said.

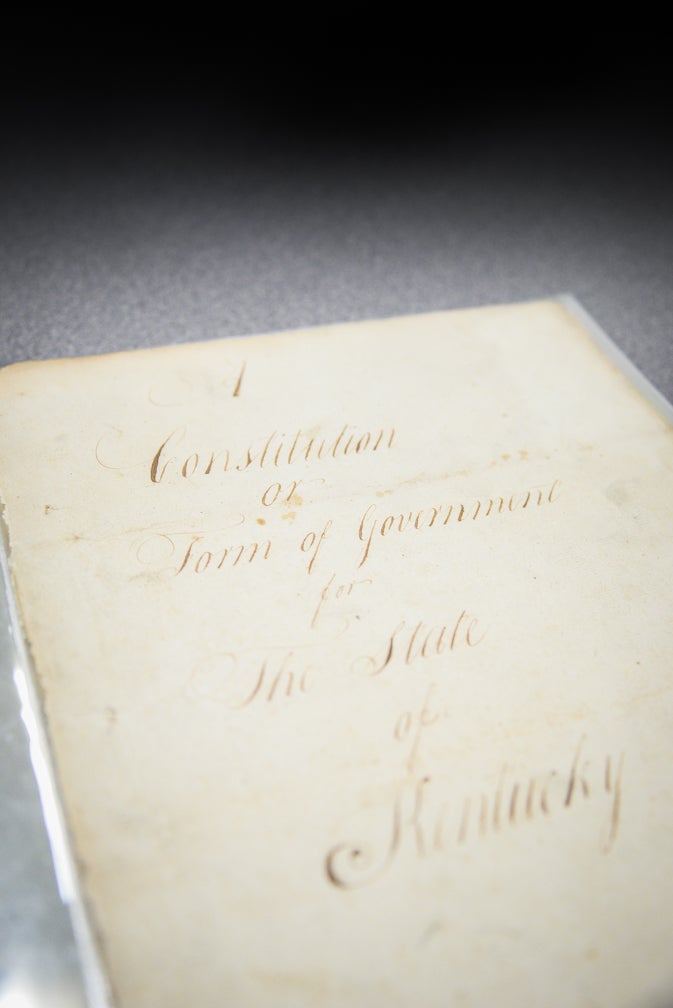

One of the documents being protected by the low temperature is the original Commonwealth of Kentucky Constitution written in 1792.

Ten constitutional conventions were held in eight years, Elliot said. One of the artifacts in archival storage is a journal belonging to Thomas Todd, a clerk taking notes during the 1788-1792 conventions.

“He got bored and started doodling,” Elliot said. “To me, that makes those people like me and you. They got bored during a meeting and started doodling just like we do. It makes it a lot more real.”

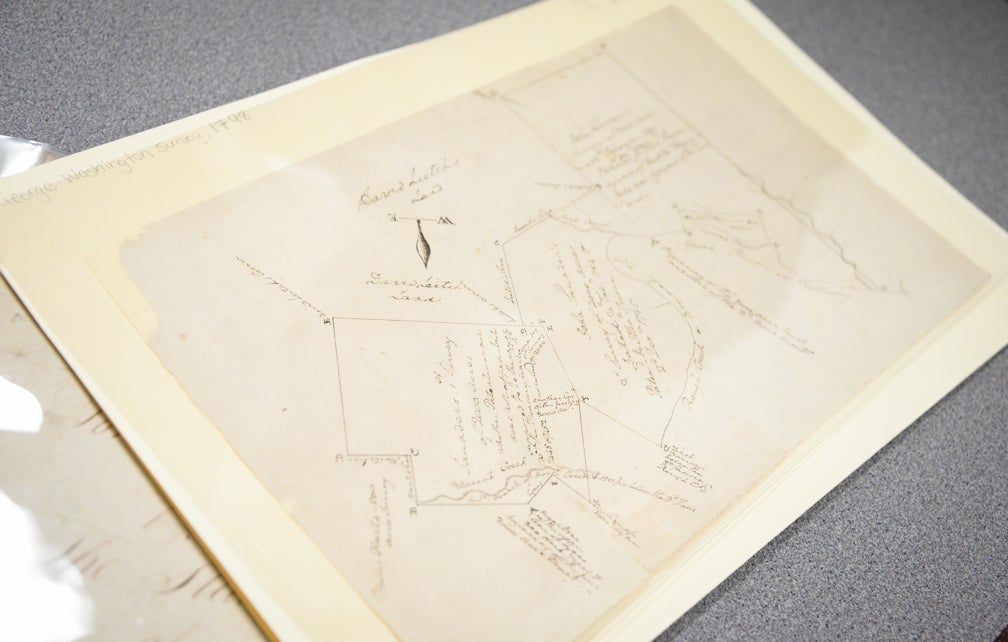

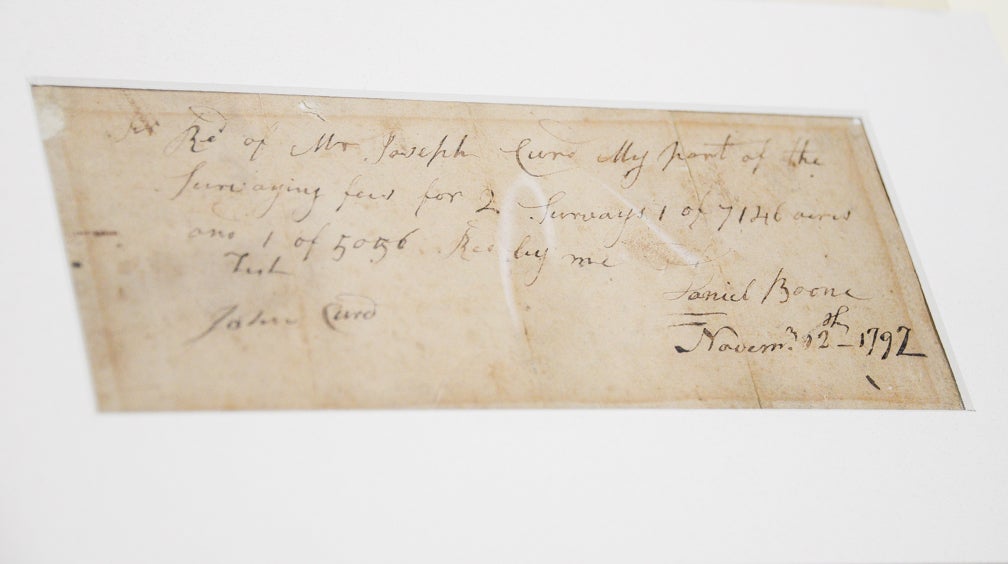

KHS also has a land survey of property purchased in Kentucky drawn by George Washington.

“He had purchased land in western Kentucky, down in what is now Grayson County,” she said. “He had purchased the land because he had heard there were iron deposits there. Buying it was an investment. He never came to Kentucky. He became president right after he bought it. He drew this plat based on previous surveys and other documents.”

Elliot said, when she gives tours of the museum, she emphasizes people living during the 18th and 19th century were not that different than modern-day people. They had hopes and dreams and families to provide for. The biggest difference between the past and the modern era is the technology, Elliot said.

“Making that connection, helping people understand that people are basically the same regardless of what century they live in, is important,” she said. “I find it comforting to know that other people have gone through the same things I have and came out the other side. I think understanding that humanity is important.”

The purpose of collecting artifacts and other people’s stories to share with other generations is to create that connection, she said.