By Chris Easterly

“Everyone’s life is a collection of moments,” said Toby Penney as she pointed to a bin stuffed with scraps of old fabric in her art studio. “Each scrap represents a moment in someone’s life. They just haven’t decided where they’re going to land yet.” Penney’s vision is to repurpose those moments into a new, living piece of art.

Penney’s workspace is an old science classroom on the third floor of the former Good Shepherd school building. The colorful studio is packed with arts supplies and large in-progress canvases. In addition to working as a full-time painter, sculptor and photographer, Penney teaches art classes here to children and adults.

Penney and her husband, Michael, moved to Frankfort from Tennessee more than four years ago. He is a chef and decided to take a break from catering and running restaurants. A realtor helped them find a house and connected them with a home school program for their daughter Gracie, now 9 years old. They were attracted by downtown’s accessibility, including restaurants and a dance studio.

“I’ve always been an artist,” Penney said. “This is Plan A.” That plan started when she was still in high school. Penney always knew she was going to be an artist. “If I wanted to eat while I was doing that, I had to figure out how to have an income from it,” she said.

In those days before social media, Penney marketed herself by mailing slides and expensive packets of her work to galleries. Over time, she developed relationships with galleries across the country, including Georgia, Iowa and North Carolina. She has also worked with galleries in Australia and Europe.

Penney’s primary income is from sales of her paintings and sculpture. She has also branched out into photography. “My aunt was a private investigator and documented everything, so I’ve had a camera in my hand since I was a kid,” she said. When Penney’s daughter was born, she started photographing soccer practices, playground visits and other events. People started asking for the photos, they were featured in publications, and a gallery in Atlanta asked for exclusive permission to sell them.

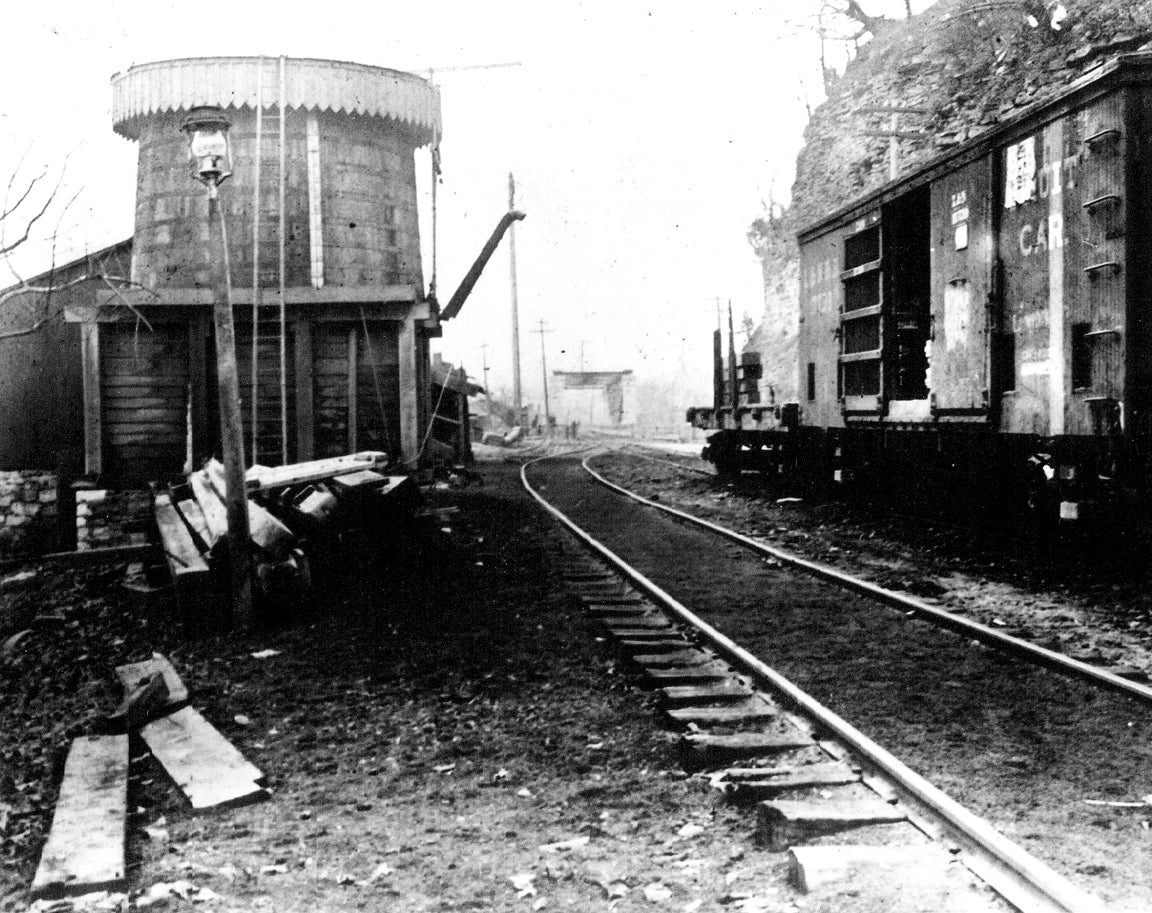

Penney found her primary inspiration years ago in unlikely places: abandoned industrial sites. “I lived in cities and river towns where there were quite a few of them,” she said of these sites. “They informed the growth and the demise of the cities. So there was this interesting relationship between growth and regeneration and moving on and ‘What do we do with our leftovers?’”

Penney started photographing the sites. She and her husband had their first date at an abandoned copper mine in Tennessee. “There was this whole community that had been there and you could tell they had just walked off,” she said, recalling an antiquated doctor’s office, late19th-century medical equipment and files left behind. “It was an amazing space. I started focusing more on connections where textures overlapped, where rust or age had developed.”

At the time, her budget for materials was low, so she started using industrial paints and house paints that people were throwing out. Looking for more thickness and body for her paintings, she started adding reclaimed papers and fabrics. “I started feeling the value those items had in their own right,” Penney said.

Her fascination with the abandoned crystallized into a personal philosophy. “It frustrates me how disposable almost everything in our society feels,” Penney said. “Overconsumption is something I see as a longterm challenge for everyone.”

She mentioned, for example, that we might buy a sandwich but don’t think about the wrapper. Who made it? What did they infuse of their life into it? “Every object has a history of its own, so we give it respect,” she said. “I take castoff items and revalue them basically.”

Within the last year, Penney has been collecting leftover paper, grocery receipts, brochures and free magazines. All are raw material for her mixed media paintings. “We have objects that can be repurposed everywhere,” she said.

Gracie is an artist as well. She recently sold two items, a painting and a pottery piece, at a show at the Grand Theatre. Gracie has her own workspace in her mother’s studio. Penney pointed to a merry clutter of papers and supplies near the studio sink. “All this other disaster is my disaster, that middle disaster is hers,” she laughed.

Gracie has adopted her mother’s personal philosophy along with her art talent. “She takes dolls that she feels like nobody loves and she will modify them,” explained Penney. If the doll lacks an arm, Gracie makes it a prosthetic and gives it a new identity, such as a superhero or a Greek goddess.

“We live reclaimed lives,” Penney said of her small family. She wears thrift store clothes and drives a 30-year-old Volvo. They prefer to spend their money on overseas family camping trips where Penney works on her art.

The family is currently deciding on their next travel adventure. Penney hopes to establish a space in France where disenfranchised artists, particularly working mothers, can enjoy a residency.

“I’m never okay with not being productive and not practicing,” Penney said. She holds the same philosophy for both art and life, noting that a painting is never finished.

“If I don’t sell them or they don’t go behind glass, I might pull it back out and work on it again because life keeps happening and things keep adding up,” she said. “The point of it is to continue life. It’s in progress, it’s living. I’m going to have all these other experiences I can add to it later.”