The recent rock fall at the Taylor Avenue rock quarry led Dr. Gene Burch and I to reminisce about how in the 1960s the quarry had been a civil defense radiological fallout shelter. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the federal government began to establish civil defense fallout shelters throughout the United States.

The program was managed by the Office of Civil Defense located in the Department of Defense. Other countries at this time also established radiological fallout shelters, including Sweden and Switzerland. The purpose of a radiological fallout shelter was to protect people from the effects of radioactive fallout that had been produced by the explosion of an atomic bomb.

These fallout shelters did not protect against blasts or direct radiation. Each fallout shelter, in theory, contained enough food, water and medical supplies to care for the population assigned to that shelter for a two-week period. I seem to recall that the Taylor Avenue quarry fallout shelter had an assigned population of 2,000 individuals.

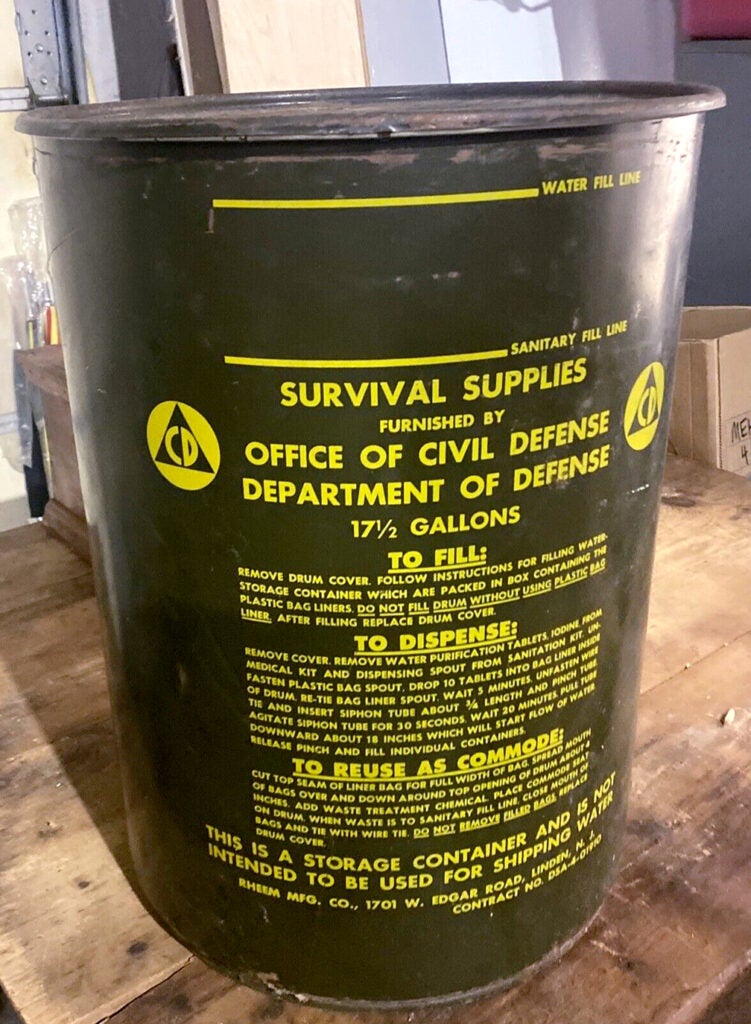

What was stocked in the quarry for use by the population sheltering in the fallout shelter? There were a number of items. There were 17.5-gallon metal drums, which were to be filled with potable water during time of crisis. These drums also contained water purifying chemicals that could be added to the potable water.

There were also 17.5-gallon cardboard sanitation barrels that each came with a 20-gallon plastic bag. The barrels were to be used as commodes and contained a toilet lid, toilet paper, hand cleanser, paper towels, sanitary napkins and a bottle of pure iodine for pouring onto the mess in the barrel for disease control.

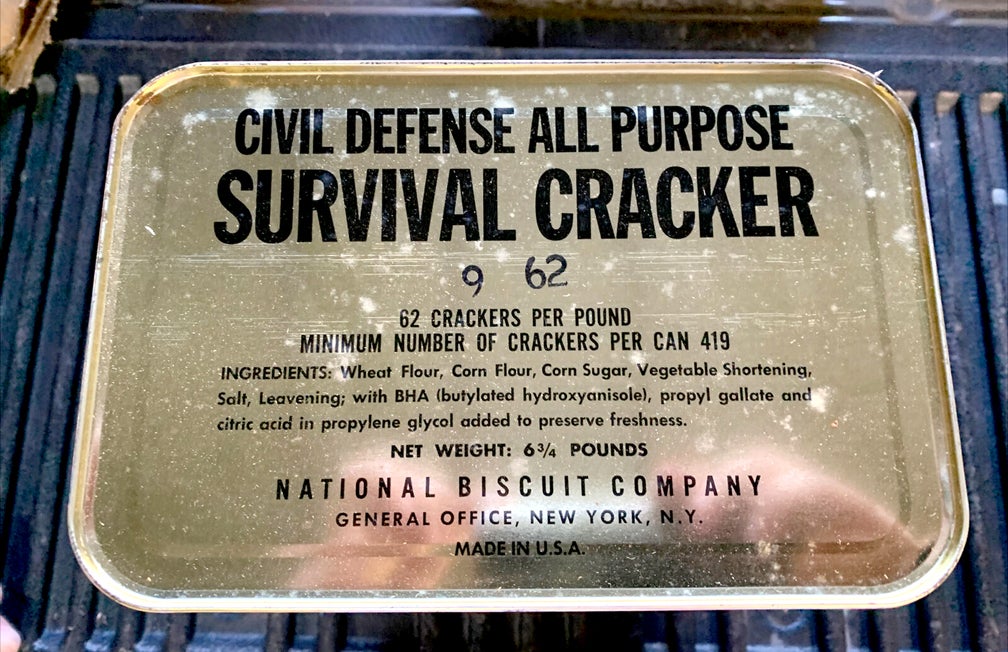

For food, two items were provided — fortified crackers and carbohydrate supplemented hard candy. Each person was to receive two fortified crackers and one piece of hard candy daily. If I remember correctly, these items would provide an individual with 2,500 calories. Understand, they were not standard grocery store items but specially fortified pieces of food.

The medical chest held a large variety of medical supplies to handle most injuries or illnesses within the shelter’s population. Little thought was given that many of the items in the medical chest had a Black Market value, particularly the pain control drugs. Therefore, during the 1970s, the medical chests became prime targets for those involved in drugs. As a result, by the mid-1970s, the medical chests had been reduced by the government to little more than first aid kits.

Also among the supplies in the fallout shelter were a variety of radiological monitors and dosimeters for measuring real time and long-term radiological fallout dosage rates. Each county in Kentucky had, in theory, a trained group of volunteers to manage each of the fallout shelters holding more than 100 individuals.

Between 1980 and 1990, the federal government closed all the radiological fallout shelters. The material in the shelters was declared surplus and turned over to the states to dispose of. As I recall, most of the metal drums were snapped up by farmers who found them to be wonderful airtight containers to store feed in. They were rodent proof. The water treatment chemicals were collected by local sanitation departments.

The cardboard sanitation barrels were robbed of their toilet paper and sanitary napkins, which were distributed to various government agencies for use in restrooms. The hand cleaning solutions found their way to various maintenance garages. The iodine was collected by the health departments.

The fortified crackers were at first given to farmers to feed their hogs, but USDA ruled that these crackers were unsafe for use as animal feed. The fortified crackers were then shipped to India and Bangladesh to feed flood victims. The hard candy was shipped to various county and state jails and soon gained the name “jail candy.”

Some of the 1,000 calories per piece of candy were given out in state offices. Soon state employees were wondering why they were putting on so much weight. Oops! The candy was quickly withdrawn from state offices. The medical kits were given to local health departments and Red Cross Chapters. As for the radiological detection and monitoring devices, they were gathered up and taken to landfills for disposal.

I know that as late as 2005, catches of fallout supplies were being found in different locations around the commonwealth. The Capital City Museum has on display a sanitation barrel and a can of survival crackers that came from the old Frankfort fire station on East Main Street.