One of the minerals all humans need to survive is salt. Until modern refrigeration, salt was used to preserve meat, for without salt, any meat not eaten within 24 hours after the killing of the animal would start to turn rancid and soon become unfit to eat. Salt was also needed within the human body, if the body was to remain healthy. Strangely, too much salt or too little salt within a human body can lead to death. Just like the porridge in the tale of Goldilocks, the portion of salt within a human body could not be too much or too little, it had to be just right.

The early settlers in Frankfort faced a problem in obtaining salt. Salt was found at various “Licks” in Kentucky: Blue Lick, Paint Lick and Big Bone Lick to name a few. Here, water containing salt bubbled to the surface. The salt laden water was collected and placed in large iron kettles. Woodburning fires were built under the kettles causing the water to evaporate and leave behind salt. As might be expected, hundreds of gallons of water had to be boiled off by burning countless cords of wood to produce a pound of salt. The salt then had to be scooped out of the kettle and loaded into barrels to be transported by packhorse or wagon to market, Frankfort being one of these markets.

In 1801, the Kentucky Legislature, recognizing the importance of salt to the wellbeing of Kentucky’s economy, passed a law that allowed salt manufacturers, when taking their product to the market, to freely pass over private property without the property owner’s permission.

Now, among the Commonwealth’s salt works, was Langford Works, which started production circa 1795 on Goose Creek outside of Manchester, Kentucky. The salt from Goose Creek was at first taken to market over the Wilderness Road by pack horse and wagon. This was an expensive way to move the salt to market. Circa 1805, the Langford Works, now known as the Goose Creek Salt Works, began to move its salt to market by water. As it was produced, salt was put in storage to move to market on the Winter Tide.

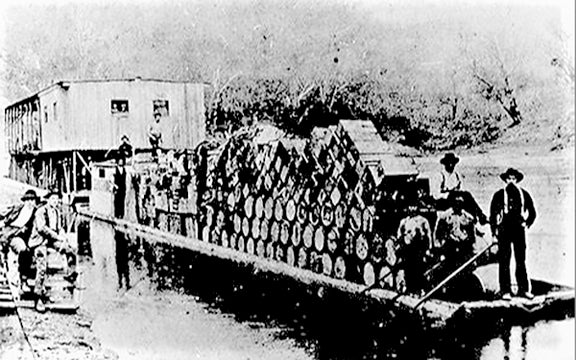

A splash dam was built across Goose Creek to form a pool. In the pool was launched locally built push boats. As winter rain and snow melted off causing a rise in the tide along Goose Creek and the South Fork of the Kentucky River, barrels full of salt were rolled onto the push boats. When water began to go over the top of the splash dam, the dam was broken and the push boats began to float down river on the tide.

Along the way to the Ohio River, push boats with their salt loads were dropped off at Hazard, Jackson, Beattyville, and other riverside landings, to sell their salt. Then, sometime in February or March, the salt tide would deliver push boats loaded to the brim with barrels of salt to the Frankfort public landing. The salt tide was an event looked forward to by both merchants and everyday citizens. Salt delivered to Frankfort by the salt tide was much cheaper than that delivered by horse drawn wagon.

Barrels of salt would be stored away until autumn when the annual thinning of animal herds would take place. The stored salt would be used to preserve the pork and beef needed to survive the winter. The salt also was used to replace the salt lost by the human body and animals as a result of sweating while out in the summer heat.

The salt tide was an annual event in Frankfort until 1861. In August of 1862, the Federal Army destroyed the Goose Creek Salt Work as they retreated north from Cumberland Gap following the invasion of Kentucky by Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s Confederate troops. Thereafter, for the remainder of the 19th century, salt was delivered to Frankfort by the railroad, and the salt tide faded from the memory of Frankfort citizens.

Next time you are downtown, stop in at the Capital City Museum and visit the Kentucky River Room.