By Chuck Edwards

The Beginnings: The Kentucky Frontier

Kentucky’s first European settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains from Virginia into Kentucky. They then journeyed westward into central Kentucky by following the paths, or traces, created by millions of migrating buffalo. One of the most important of these traces was the Alanant-o-Wamiowee, which crossed the Kentucky River at Leestown, near Frankfort, at the site of the present-day Buffalo Trace Distillery.

Most of the settlers who followed these trails were farmers, and they quickly learned that corn grows well in Kentucky and that corn could be converted to whiskey. In short order, the new immigrants were making corn liquor — moonshine. The left-over spent grain was then fed to their livestock and the whiskey was bartered for other goods and services. In effect, a barrel of whiskey, for all practical purposes, was a barrel of cash. Furthermore, corn, at 56 pounds a bushel, was not easy to export, so the locals found whiskey easier and more profitable to export. By the early 1800s, there were thousands of farmers in Kentucky and most of the farmers were making whiskey. If you lived in Kentucky at that time, most likely, you would have been a farmer distiller.

As America continued its western expansion, the oak barrel served as the primary storage and cargo container of the day, which presented a significant problem to the early Kentucky distillers. Simply put, barrels that contained items like pickles or fish produced nasty whiskey. To eliminate the foul taste and odors, farmers burned or charred the inside before filling them with whiskey. These barrels were then rolled down to a river and placed on flat-bottomed boats. It was a nine-month journey down the Kentucky, Ohio and Mississippi rivers to their destination of New Orleans, Louisana. By the time those barrels reached New Orleans, they had aged whiskey. This whiskey became quite popular and named after its place of origin — Bourbon County, Kentucky.

The Peppers on Glenn’s Creek

Elijah Pepper settled in Kentucky around 1790. Elijah and his brother-in-law, John O’Bannon, built a small distillery in Versailles, just below the spring that is the primary source of Glenn’s Creek. They produced whiskey in a limited way until 1812, when Pepper purchased a large tract of land several miles downstream and began growing his farm and distillery. The farm eventually became today’s Woodford Reserve Distillery.

After Pepper’s death, his wife, Nancy Ann, ran the farm and distillery, and in 1838, their son, Oscar Pepper, purchased the distillery from his mother. Oscar then branded the distillery Old Pepper, and more significantly, hired James Crow to oversee whiskey production. Because Oscar did not prepare a will, his estate was in disarray at his death. Oscar’s widow entrusted her oldest son, James, with the responsibility of running the distillery. James, however, was still a minor, so she had EH Taylor Jr. appointed to be his legal guardian. Ironically, with the help of EH Taylor, James later sued his mother for ownership of the distillery.

James C. Crow

James C. Crow was an enigma. Not much is known about the man, but there are several lingering myths about Crow. For instance, Crow was not a medical doctor. There is no evidence he studied or practiced medicine. The doctor was attached to his name as a part of a 1950s ad campaign. Likewise, Crow did not invent the sour mash method. Others used the technique. Furthermore, no image exists of his likeness. This image was most likely a part of another marketing effort.

What we know is that James Crow was born in Scotland around 1787, during a period of scientific and industrial innovation. By the early 1820s, Crow was attending classes at Scotland’s leading academic institution — Edinburgh University. Here he studied natural sciences, and his professors were the world’s leading brewing and distilling authorities.

After completing his studies, Crow emigrated to Philadelphia in 1823, and by 1826, to Woodford County. There, he operated as an itinerant distiller for several local farmers, including Willis Field on Grier Creek and Anderson Johnson on Glenn’s Creek. In 1840, Crow settled at the Old Pepper Distillery, where he worked from 1833 until 1855 for Oscar Pepper.

During that period, Crow perfected his methods of making double-distilled sour mash whiskey and schooled numerous future distillers in his methods. In 1855, he returned to the Anderson Johnson Distillery and within a year he died in the house Johnson had built for Crow and his family. Crow, a highly educated, successful and well-paid man, never owned a distillery nor his own home.

Both the Pepper Distillery and the Anderson Johnson Distillery continued operations using the Crow method. Crow’s techniques (copper stills, double distillation and sour mash fermentation) would spread to about 12 distilleries in the Frankfort/Millville area by the time Taylor picked up the mantle.

Edmund Hayes “EH” Taylor Jr. (1830-1923)

EH Taylor, born in Columbia, Kentucky, near the Mississippi River, was the oldest of three children. Tragically, his early childhood was altered by a series of unfortunate events. As a result, the five-year-old Taylor was moved to Frankfort and left to the care of his uncle of the same name, Edmund Haynes Taylor.

After finishing his education, he joined his uncle at the Farmers’ branch bank in Frankfort. His uncle was the cashier, or chief financial officer. During his youth, Taylor was introduced to banking and finance, added the Jr. to his name to avoid confusion at work, and was likely introduced to James Crow.

As a young adult, Taylor took a position as the cashier in a Versailles bank until he started his own bank. Later, he moved to Missouri to start a commodity trading company, and eventually returned to Frankfort and traded grain and tobacco. Before Taylor’s entrance into the whiskey business, he had a solid background in finance and commodities.

A man of his times

In his mid-30s, Taylor could not have picked a more perfect time or place to enter the whiskey business. The Civil War had shuttered half of American distilleries. Seventy-five percent of American whiskey was produced in other mid-western states, and most of that was of inferior quality. In 1871, America was producing approximately 4.3 proof gallons of whiskey per year, and within 20 years, U.S. whiskey production skyrocketed to 29.3 million gallons. Strategically, Taylor could not have been better situated.

At the end of the Civil War there were four different grades of whiskey — common or white whiskey, which sold for less than $1 a gallon; Kentucky bourbon or rye, which sold for $2 a gallon; sour mash whiskey, which sold for $3 a gallon; and whiskey made according to the Crow plan, which sold for $5.50 dollars per gallon. Of the 600-plus distilleries in the United States, there were only about a dozen operating using the Crow plan.

As with the rest of the American economy, technological advances revolutionized the whiskey business. Railroads improved supply chains, which enabled both raw materials and final products to be distributed efficiently throughout the country. Better grains and fermentation techniques doubled the yield of a 56-pound bushel of corn from 2.5 gallons to 5 gallons. The use of all copper continuous stills, increased production, lowered cost and improved quality.

Taylor saw the opportunity in the whiskey business, so he joined Gains, Berry, and Company. Their vision was to unite Crow’s methods and modern technology to produce the world’s finest whiskey — Old Crow’s hand-stirred, copper-distilled sour mash whiskey. First, they leased the Old Pepper Distillery (Taylor was now James Pepper’s legal guardian) and the Johnson Distillery (just downstream from Old Pepper, and where Crow had also distilled) and began production of Old Crow. Next, Taylor was sent to Europe to examine modern European distillation practices. Finally, upon Taylor’s return, they built two new state-of-the art distilleries — the Old Crow Distillery, adjacent to the Johnson Distillery on Glenn’s Creek; and the Hermitage Distillery, in south Frankfort on the Kentucky River.

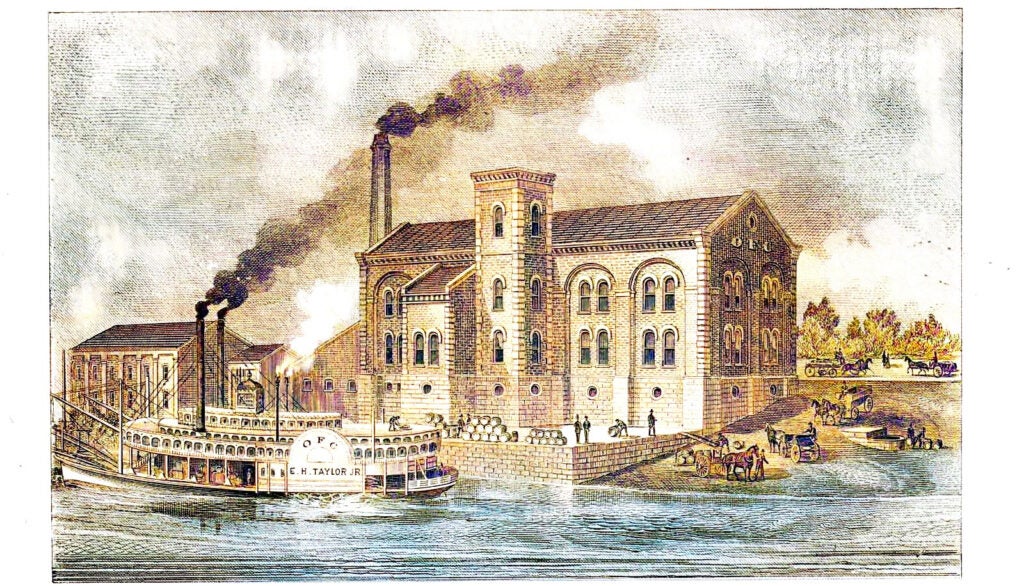

As construction was nearing completion at the two new distilleries, Taylor purchased the Leestown Distillery, currently the home of the modern-day Buffalo Trace Distillery. Gains and Berry, now the WA Gaines Company, saw this as a serious conflict of interest and gave Taylor the choice to sell his shares in the company. Taylor was more than happy to oblige! He took the $33,000 buyout and refurbished the neglected Leestown Distillery.

Tailored whiskey

Next, Taylor hired Crow’s former assistant James Mitchel to operate his distillery and he rebranded it the OFC Distillery, for Old Fire Copper. Copper stills were not in widespread use at that time. Most of the farmer/distillers used three-chambered wooden stills, which produced an inferior whiskey. Copper stills were expensive, but copper was, and still is, the gold standard in the whiskey business. Taylor, who was always mindful about marketing, was very intentional when he included copper in the name of his new distillery.

Ultimately, Taylor’s goal was to build, own and operate the most modern distillery in the business, but the Leestown Distillery did not meet this standard. To achieve his goal, Taylor needed a large amount of capital. Therefore, he solicited the support of whiskey wholesaler and bottler, George T. Stagg. Then, Taylor and Stagg had the distillery torn down, rebuilt and in Taylor’s own words, “not a cent of expenditure was withheld.” In 1873, Taylor’s state-of-the art OFC distillery was complete. Taylor, bullish on the whiskey business, purchased no less than six other distilleries over the next nine years.

Prior to the construction of the OFC Distillery, the country had experienced a period of economic expansion and prosperity, but that ended as the OFC was completed. The 1873 Financial Panic and the resulting long depression, created tight money supplies and the sale and price of whiskey plummeted, particularly in the premium brands. So, nine years later in 1882 when the OFC Distillery was struck by lightning and leveled by fire, Taylor found himself in financial crisis. After the fire, reconstruction plans were drawn up, rebuilding began, and the new much larger distillery was completed within a year. However, Taylor found himself unable to service his nearly $500,000 debt.

Taylor, in serious financial trouble, was forced to sell all of his distilleries and his shares in the OFC Distillery to Stagg. Because Taylor’s name, reputation and label sold whiskey, Stagg made Taylor vice-president of production. However, Taylor was eventually forced to sell his remaining one share in the OFC Distillery to Stagg, and Stagg agreed to sell the J. Swigert Distillery back to Taylor. It was a contentious exit agreement, and the men were embroiled in bitter lawsuits for years after Taylor’s departure.

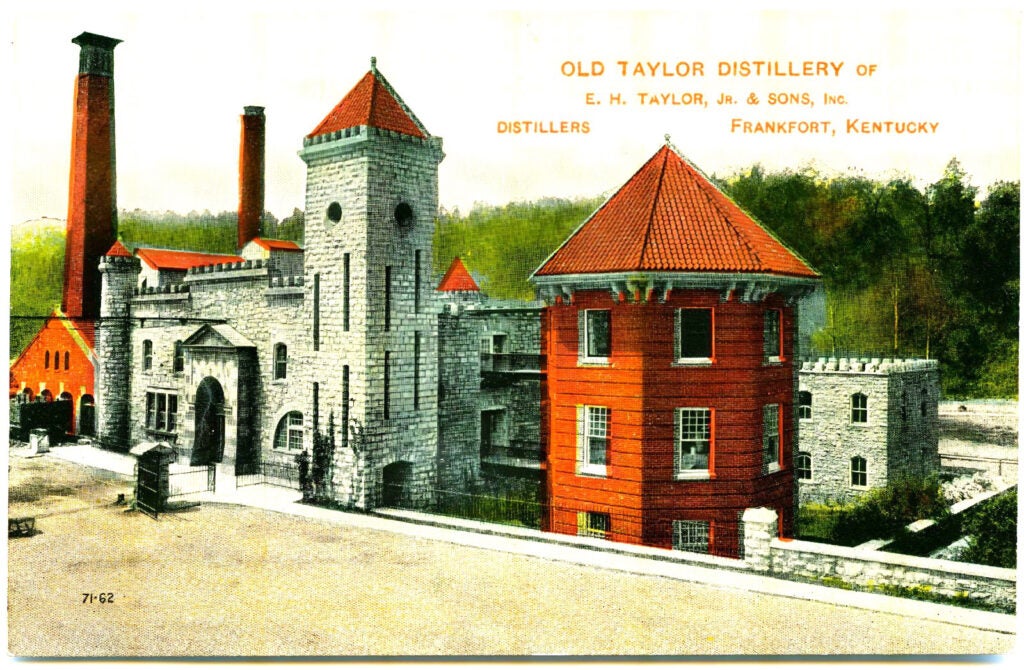

A king in his castle — Old Taylor Distillery

Taylor, starting over at 57, was an American aristocrat, born into a wealthy, influential family and related to two former presidents, Zachary Taylor and James Madison. As such, he was a flamboyant and natural whiskey salesman with a taste for the extravagant.

In January 1887, his credit now clear, Taylor had his repurchased Johnson/J. Swigert Distillery demolished to make way for the new state-of-the-art Old Taylor Distillery. The distillery, however, would be concealed within the confines of a medieval castle complete with crenelated battlement walls and turrets. Taylor’s palace, Taylorton, was an 82-area campus with 21 buildings, a train station, public gardens and a Roman-like peristyle colonnade enclosing a 140,000-gallon pool the shape of a keyhole. The Old Taylor Distillery was a destination.

Taylor’s efforts were frustrated yet again by another monetary crisis. The 1893 Financial Panic sent the economy into another depression and whiskey consumption fell by 30%. Assessments were taken out against the distillery. Creditors placed Taylor’s liabilities at almost $350,000. Because Taylor’s trademarks were held in a separate company, Taylor was able to lease the distillery and maintain production for a time. The property was eventually sold at auction for $16,500 to Taylor’s son, Jacob Taylor, the sole bidder, and at 67, Taylor started over, yet again.

As the economy recovered and sales returned Taylor built a home, Thistleton, a Queen Ann mansion on 160 acres about three miles from today’s capital. Over the ensuing years, he grew the estate to 900 acres. As he approached 70 years old, Taylor purchased a farm close to the distillery and built one of America’s most premiere Hereford farms and over the ensuing years grew it to 3,000 acres. Today, it is known as Ashmore Stud, currently the home of two Triple Crown-winning stallions.

By 1919, Old Taylor was the bestselling bottled-in-bond whiskey in the world, and Taylor’s three sons, Jacob, Kenner and Edmund W., had gained operational responsibility for Old Taylor Distillery. The distillery continued production until prohibition, and Taylor died in 1923 at 92 years of age a very wealthy man.

The evolution of bourbon on Glenn’s Creek

Frontier whiskey was crude and unpretentious, produced by thousands of farmers as a practical remedy to the rigors and travails of frontier life. James Crow transformed this primitive spirit, at Oscar Pepper’s farm along the banks of Glenn’s Creek, into what we know today as bourbon. Crow, more than anyone else, could be credited as the inventor of bourbon. Taylor combined Crow’s methods of copper stilled sour mash whiskey and scientific methods with modern manufacturing techniques, and brilliant marketing strategies, to create the modern bourbon industry we know today.