From 1792 to 1847, letters mailed in the United States did not carry pre-paid postage stamps. The cost of delivery, based on weight and distance, was written on the envelope at the mailing post office. The recipient was then expected to pay the cost upon delivery.

The U.S. Post Office quickly found itself sinking into debt as the recipient of letters often refused to pay the postage, or the recipient simply could not be found. In 1847, to rectify this problem, the sender of a letter had to prepurchase stamps of enough face value to cover the delivery cost of the letter.

These postage stamps had to be affixed to the envelope before being handed in to the post office. To prevent the stamp from being soaked off the envelope by the recipient and then being reused, the envelope, upon being received at a post office, had its stamp hand canceled.

This hand-held canceling device had permanently engraved in it the name of the town and state the using post office was located in. Then, by changing a removal insert daily, which was located in the center of the hand canceling device, the month, day, year, and time the letter had been canceled could be recorded.

By 1890, with the advent of the penny postcard, the U.S. Post Office was being buried in over 5 billion letters and postcards annually. An army of men was needed to hand-cancel all of the mail arriving daily at post offices across the United States. Therefore, that year the U.S. Post Office began to solicit ideas from the American public and business establishments on how to automatically machine cancel postcards and envelopes, thus speeding up the processing of the mail.

In 1896, two local Frankfort men, John Milam and Samuel Holmes, turned their creative talents to producing an automatic stamp canceling machine. By 1897, they had perfected such a machine and offered six of their automatic stamp canceling machines to the U.S. Post Office for testing.

Unfortunately, we do not know what these machines looked like or how they operated. We do know, however, that four were retained in Frankfort; one went to Louisville, Kentucky; and one was sent to Lytle, Georgia. Why one machine was sent all the way to Lytle, Georgia, is unknown. The Frankfort Post Office was, at this time, located at the corner of St. Clair and Wapping streets in the building that now houses the Kentucky State University River Study program.

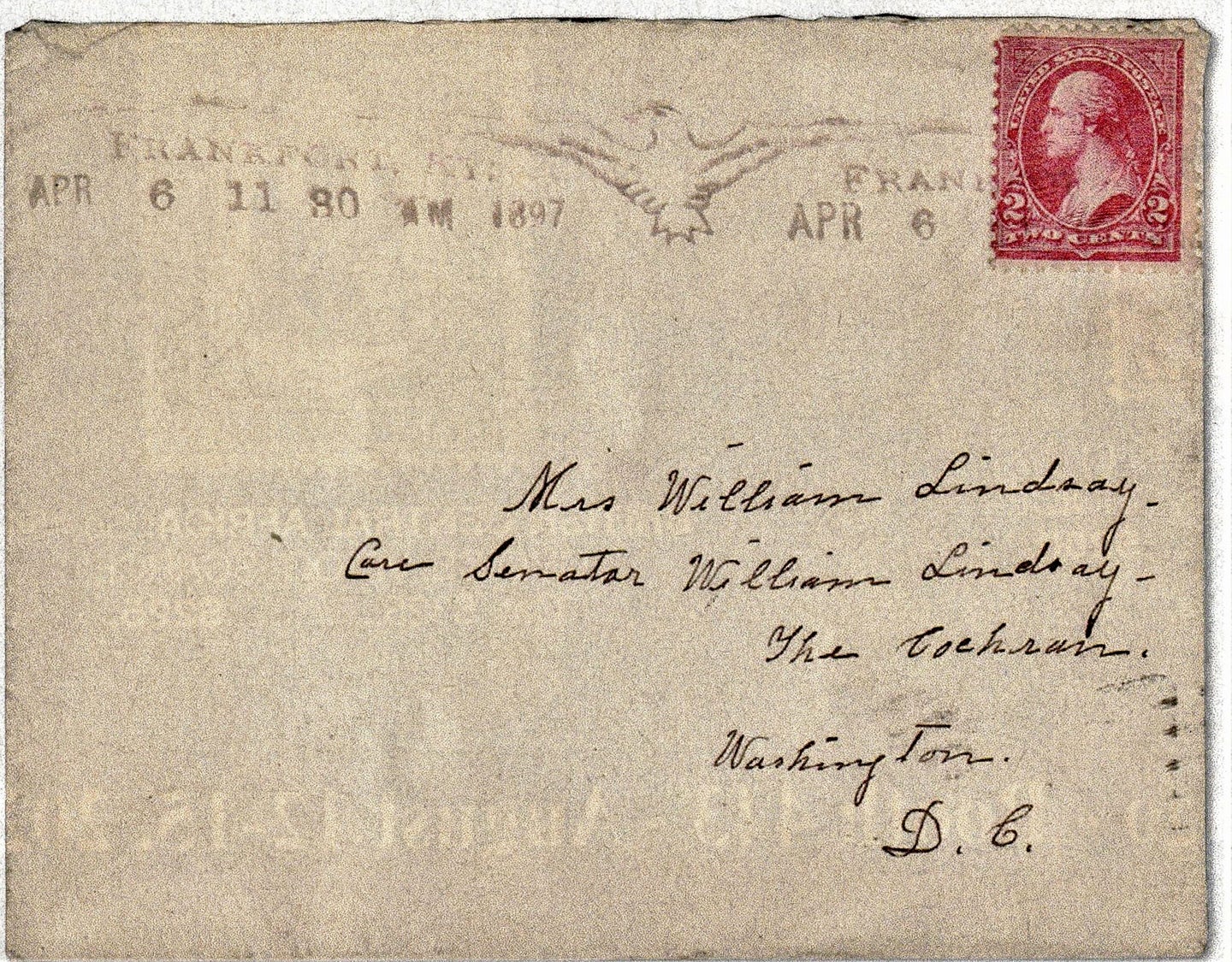

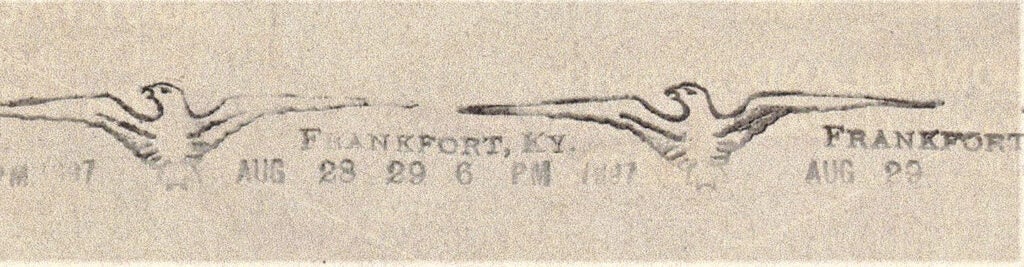

When in operation, the Milam-Holmes automatic stamp canceling machines printed a strip of ink marks across the top front of the envelope or the postcard. The Frankfort cancelation strip consisted of an eagle with out-stretched wings followed by the words “Frankfort, Kentucky,” with the date and time underneath. The machine continuously printed this banner across the front of an envelope, so it was not unusual for an envelope to have a cancelation strip containing two to three eagles.

In place of the eagle, the machines used in Louisville and Lytle had a horizontal row of five lines. All six of the Milam-Holmes canceling machines were pulled from use by the U.S. Post Office in 1899. Records are not clear as to what happened to the canceling machines; therefore it is unknown if they were returned to their inventors or just scrapped.

The end result was that Milam and Holmes failed to win a contract to supply the U.S. Post Office with any automatic stamp canceling machines. The most probable reason for not being able to secure a contract for more canceling machines was the lack of financial backing to construct the factory needed to build the canceling machines in the quantity the U.S. Post Office wanted and needed.

In 1900, the U.S. Post office awarded the automatic cancelation machine contracts to International Postal Supply Company and to American Postal Machines Company.

We at the Capital City Museum, 325 Ann St., are very desirous of obtaining any additional information concerning this endeavor by John Milam and Samuel Holmes to create an automatic stamp cancelation machine.