“Landings: A Crooked Creek Farm Year” by Arwen Donahue

Arwen Donahue has created a different kind of memoir with this book. She has used moments of work, pleasure, inspiration from her life on a farm in Nicholas County and included 130 ink and watercolor drawings to illustrate her daily reflections. Donahue and her family make a living by selling CSA (community-supported agriculture) shares of what they raise locally.

On Tuesday, March 26, Donahue recalls that the “pendulum-swing between winter and spring, the wild heave of a season’s change” as she was in labor for 36 hours. She walked up and down the farm’s lane, and also sat in the barn with the goats, “my covey of doulas.” She knew they were masters of birthing. “All in a day’s work, honey,” they seemed to say.

On Monday, April 15, Donahue declares, “I am like a crow whose eye is caught by a shiny object: I want to capture and carry it with me.” She is referring to the work of carrying water to the cows. “The small pool … is a bridge between the earth and sky. To bend and see the tall tree–tips held beneath my face as if in the furrow of a palm and then to warp it with my bucket, keeps me engaged as I walk back and forth from creek to barn.

On Saturday, June 1, Donahue talks of strawberries. “We had strawberry vinaigrette on our salads, strawberry ice cream for dessert. We delivered the berries to our customers and invited friends and family out to pick their own. Still, the patch was never more than half-picked.”

Friday, Aug. 9, Donahue has 12 half-bushel baskets of produce on the floor of her shotgun kitchen. She makes salsa, 12 pints, processing the jars in her pressure canner. She claims afterward how satisfying it is to “extract the food we grow from the desolation of time by sealing it in a jar and setting it on the shelf. They whisper enticingly to my inner squirrel.”

Saturday, Aug. 24, the CSA baskets are packed with tomatoes, green and red peppers, cabbage, chard, a variety of eggplants, squash, fresh herbs and lettuce. Week by week, year by year, the baskets reflect the work of Donahue and her family including 10-year-old Phoebe. Phoebe’s jobs include picking strawberries, gathering eggs and making sure the chickens get to safe perches for the night.

Margaret Renkl, author of “The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year,” says that this book is a “different kind of devotional. Each entry is both a love letter to Donahue’s life on a small family farm and a clear-eyed testament to its hardships, complexities and impossible trade-offs.”

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“James: A Novel” by Percival Everett

Percival Everett visited Kentucky State University in the 1980s. He grabbed my attention then, and I have been following him through his published works throughout many years. He has had many prize-winning publications and has also received many “Life Achievement” awards.

This tale follows loosely the telling of Twain’s “Adventure of Huckleberry Finn,” except the narrator is the enslaved Jim. Jim has hidden out on Jackson Island near Hannibal after he hears that he will be sold and forced to leave his wife and daughter. Meanwhile, Huck has faked his death to escape the violence of a father that only appears whenever he needs to display his hatred of Huck. Huck is ready for any kind of adventure and joins up with Jim. Together they survive for a time on the island.

Huck is all about the adventure while Jim schemes of how to raise the money needed to buy his family. When Huck picks up a rattlesnake skin, Jim warns him that the snake may come back to “claim his old skin.” That evening Jim is bitten by a rattlesnake. In Jim’s delirium, we learn that he managed to learn how to read, even though that is forbidden. Jim had been sneaking into Judge Thatcher’s library and devouring the philosophy of Locke, Voltaire and Rousseau.

Though Everett’s tale and Twain’s have a similar storyline, they are vastly different stories. Jim lives inside a mask pretending to be ignorant and using different “ruses” to make white people feel good, such as using stereo-typically poor syntax that Jim calls “incorrect, correct grammar.” It’s the language of enslaved people spoken when they might be overheard.

Twain’s tale paints Jim with courage, dignity and virtue. Yet, according to The New Republic, Everett “bestows upon him the greater, if more complicated, privilege of full (if not yet unfettered) humanity.”

Ann Padgett declares that “Everett delivers a powerful, necessary corrective to both literature and history. I found myself cheering both the writer and his hero.”

Everett allows Jim to finally declare his own self-emancipation when he calls himself “James.”

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“When We Had Summer” by Jennifer Castle

“When We Had Summer,” by Jennifer Castle, is a feel-good read that follows four teenage girls who have been best friends for as long as they can remember. Daniella, Carly, Penny and Lainie, #TheSummerSisters, spend every summer together bonding over their annual bucket list, that is, until Carly passed away.

The book explores how grief can look through the eyes of three teenage girls. As life changes for Daniella, Penny and Lainie, will their friendship be enough to fulfill Carly’s final adventure — a bucket list she wrote before she passed? Despite it not feeling the same, all three girls decide to attempt to complete the bucket list. They aren’t sure as to how their summer looks without Carly. Can their friendship survive without the glue that was holding them together?

“When We Had Summer” is a sweet coming-of-age book that delves into the challenging transition from childhood to becoming a young adult, all while juggling the loss of a friend and getting back to what being a summer sister truly means.

— Review by Krislyn Coburn, Paul Sawyier Public Library

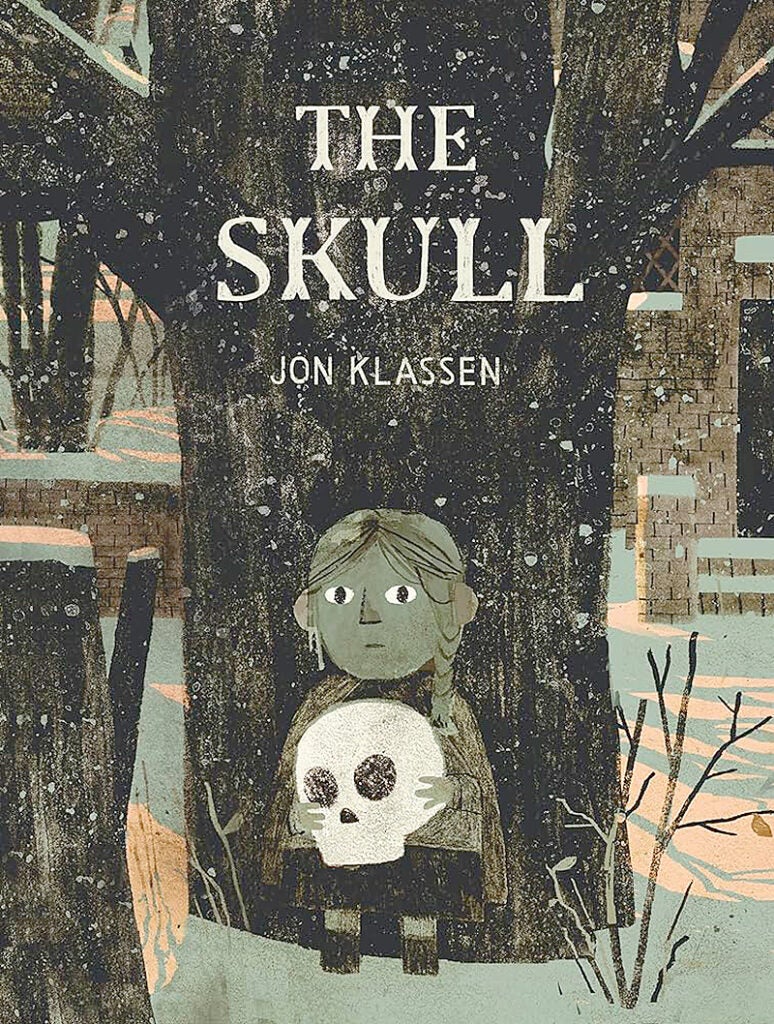

“The Skull” by Jon Klassen

“The Skull,” a retelling of a Tyrolean story of the same name, is a dive into the transformative nature of folk and fairy tales. In Jon Klassen’s version, there are no spoken magic spells or curses, no prince or princess, and not even a reward for bravery. The main conflict, when one arises, is solved through a calm morbidity quite unexpected in a children’s book.

Those familiar with Klassen’s other works, such as his debut picture book “I Want My Hat Back,” will recognize his uniquely dark style. Nearly every page is used to cinematically set the stage. His use of shadow and light in his gorgeous ink illustrations shapes a world that is mystical and eerie, creating a gothic horror for youngsters who enjoy a good spook.

The tale follows Otilla, a young girl fleeing from unknown danger. She finds sanctuary in a large house in the woods, its only occupant a sapient skull who grants her shelter and companionship. The simple narrative structure and storybook tone, along with the fun illustrations, keep the reader in a state of uncertainty and curiosity that guides them skillfully to the climax. It is a book that calls for it to be digested in full, rather than simply chewed into a pile of mush like a pear eaten by a disembodied skull. If you wax poetic about classic Grimm or feel drawn to darkly whimsical illustrations like those in Klassen’s other works, then “The Skull” is the book for you.

— Review by Alex King, Paul Sawyier Public Library