It’s impossible not to tap your toe, clap your hands and move with the music. The notes seem to ride on the breeze, reaching out from the land beyond John Harrod’s porch as he fiddled a lively tune.

“That’s a song called “Man Eater,” John explained. “Kelly Gilbert, a fiddler from Frankfort, learned this tune from Jim Booker.” (known as Fiddlin’ Jim Booker, born in 1872 at Camp Nelson, Kentucky).

Booker was one of a group of black fiddlers around Camp Nelson in Jessamine County on the Kentucky River. Their sound was like nothing John had ever heard.

“I got this music secondhand from some old white fiddlers I met who had played with these Camp Nelson Black fiddlers. It was amazing music that wasn’t like anything else,” John remarked.

Learning from the masters

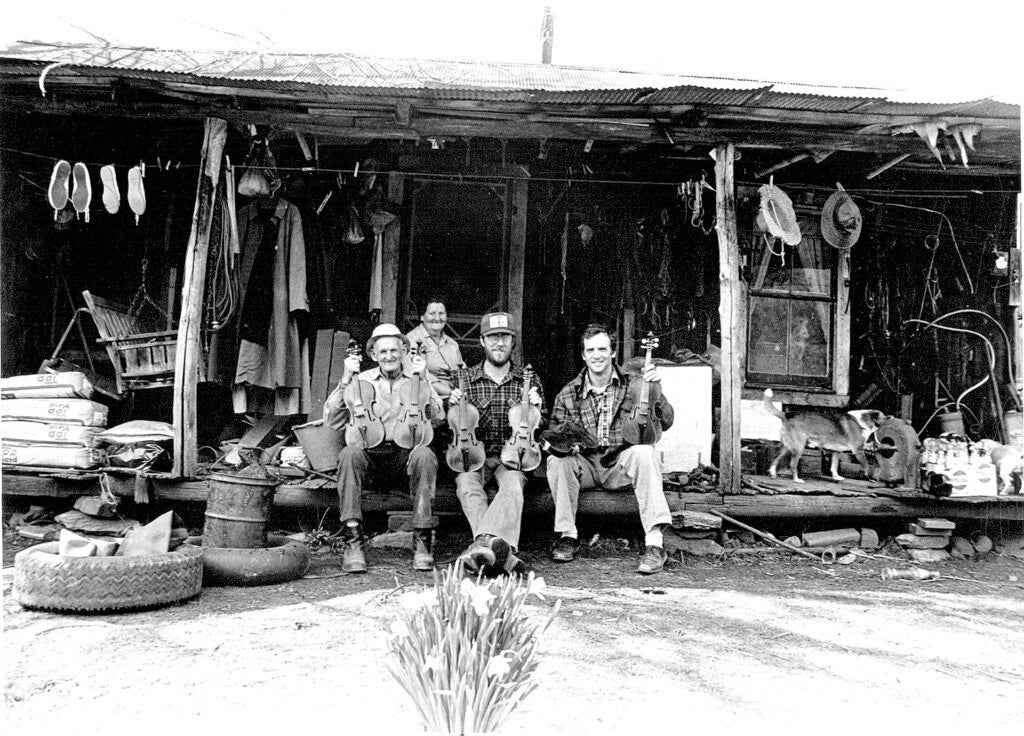

“All of the fiddlers I’ve ever met have been role models in one way or another. I learned something from all of them. One in particular, Darley Fulks of Wolfe County, probably had the most profound influence on me,” John commented. “He exemplified how serious you have to be if you want to be a fiddler. He was a thoughtful person with deep feelings that came out in the way he told of his life and talked about music.”

John will tell you that he just likes to play the fiddle. Documenting the music of traditional fiddlers allowed him to learn their type of music and be around great musicians. “Bill Livers, a Black fiddler from Owen County, was the first old-style fiddler I got to spend time with. Besides being a great musician, he was an entertainer and local celebrity. I think I learned the power of using music to disarm people and make them happy from him.”

John found that there were old-time fiddle players in Shelby County where he grew up and in surrounding areas. In Frankfort, he said there were five really good fiddlers — Pop Baker, Kelly Gilbert, Henry Thurman, Howard Phillips and Ollie Sharfe.

“I knew Pop, Kelly and Henry. Pop Baker and Kelly Gilbert had a little string band called The 65ers that would play every Saturday afternoon in the parking lot next to Harrod Brothers Funeral Home.”

Gathering music

After meeting Bill Livers, John embarked on his quest to find the people in Kentucky playing “the old fiddle music.” What he discovered was that fiddlers played distinctive sound patterns based on where they lived in the state.

“When you play traditional music, you’re connected to a person that you knew and the community they lived in and maybe where they came from,” John remarked. “Everywhere you went in Kentucky, the fiddle music wasn’t just one style. I came to see how those differences you hear across the state reflect different historical influences whether it was Scotch Irish, Black or even French. You find echoes of a certain kind of fiddle music in the parts of the state that are as different as can be.”

John’s research seemed to reveal that Kentucky’s geography influenced the sound of the traditional fiddle music in each different region.

“The Bluegrass is a little more open and that makes for a happier, more danceable sound. In the hollers, there’s a lot more loneliness and sadness in the sound of the music,” John said.

“Along the rivers, the fiddle sound was impacted by the more cosmopolitan group of people going up and down the river so you hear French, German and other influences in the music. When you put together the ambiance of the people, place and history with the music you can see and feel it.”

“Maybe my name will be remembered for a while in this tradition, but I believe that we, as individuals, merge and disappear in the music as it travels through time, and that’s immortality for fiddlers.”

John Harrod

For more than 20 years, John sought out traditional musicians across the state, learning their styles, getting to know the culture and history of the area and recording their music. His extensive collection is housed in the Berea College Special Collections and Archives and at the Kentucky Center for Traditional Music at Morehead State University.

According to the Berea Library Archives’ website, the collection consists of “200 audio field recordings and 88 video recordings of interviews and performances documenting the repertoire and playing styles of several dozen Kentucky fiddlers, banjo players and singers. The recordings preserve the singing and playing of musicians mostly from the eastern half of the state. Many of them have since passed on and in several instances the tunes and playing styles documented date well back into the 1800s.”

The library entry described John Harrod as “an able musician and one of the leading documenters of older style traditional music in Kentucky, particularly its strong fiddle tradition.”

Teaching and playing

John teaches fiddle lessons to students at home and at his alma mater, Centre College; at the Cowan Creek Mountain Music School in Letcher County; and at other music camps and festivals.

“Teaching comes pretty natural because I was a history and English teacher in my professional career,” John explained. “I think I’m more effective teaching music than when I taught history and English. Those subjects were important but, with music, I’m showing people one way to be happy. Instead of being about knowledge, it’s more about a way of being.”

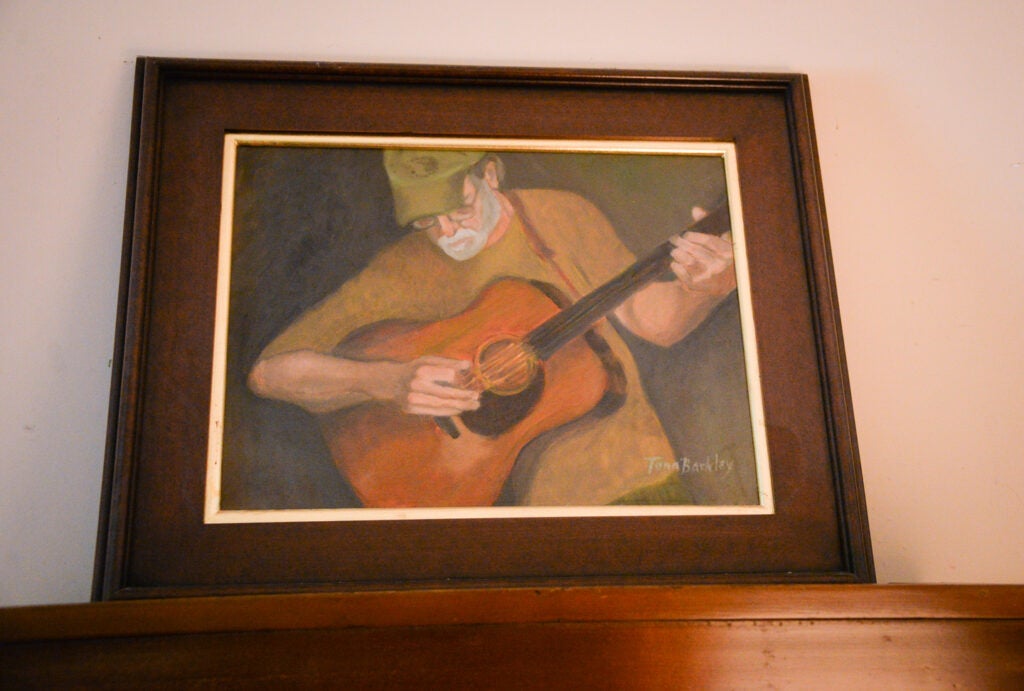

John and his wife, Tona, who plays guitar and banjo, perform with Kentucky Wild Horse, a band that started more than 20 years ago.

“The people I know in the music world are the happiest people. I feel like I’m happier now at age 78 than I’ve ever been because I’m with friends and people who play music,” John said. “Music does bring people together in a way that avoids the pitfalls of political and religious divisions. If you look deeper, it (music) can tell you a lot about the history of a place — how people lived, what they valued, and most importantly, how they felt about life because music is a direct connection to peoples’ feelings.”

John and Tona live near Owen County in a home that John built over the course of 15 years. They enjoy living in Kentucky.

“I like living in the place where my family has been since the 18th century,” John commented. “The longer and the better you know a place — its natural history, its human history, its people and their communities, the more you love it. I guess that’s the meaning of home.”