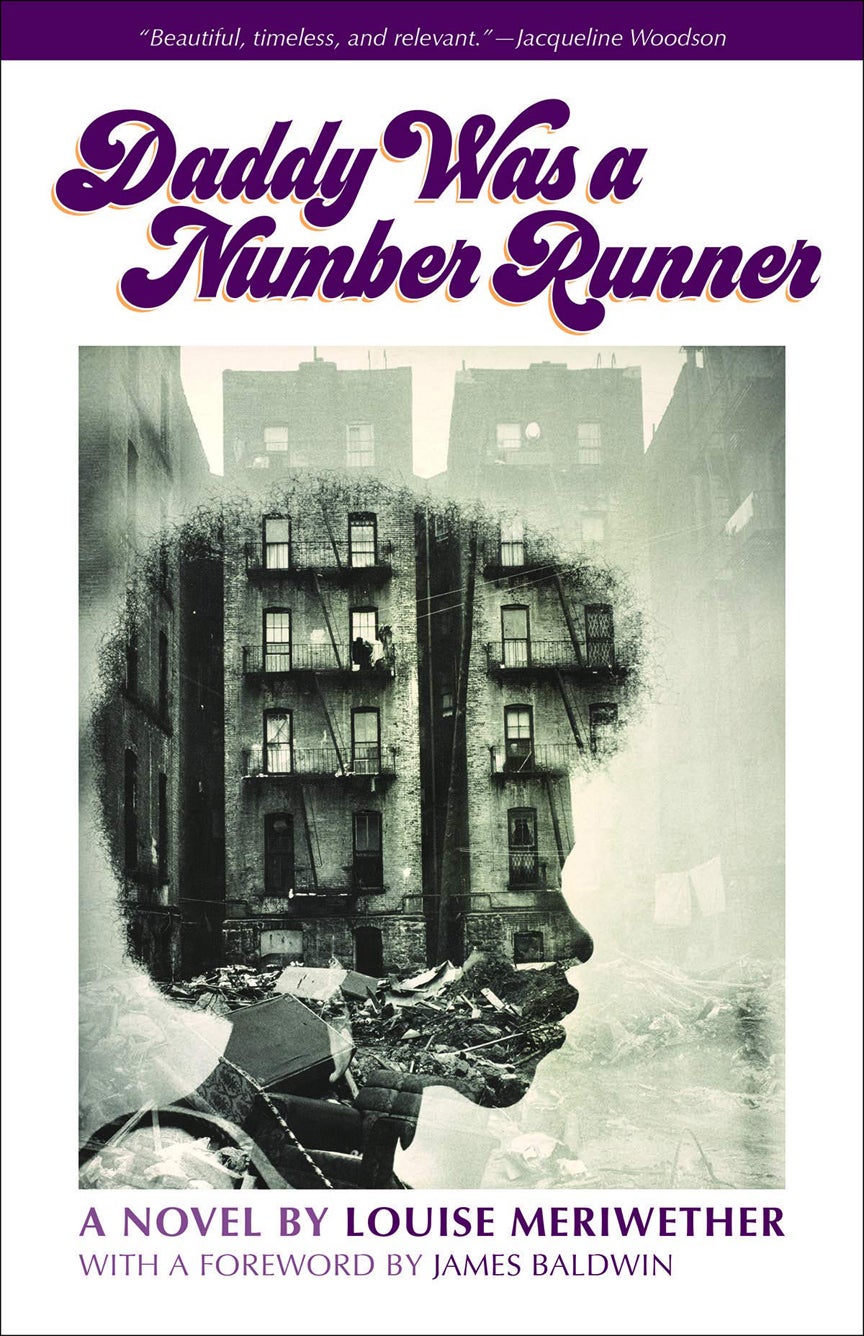

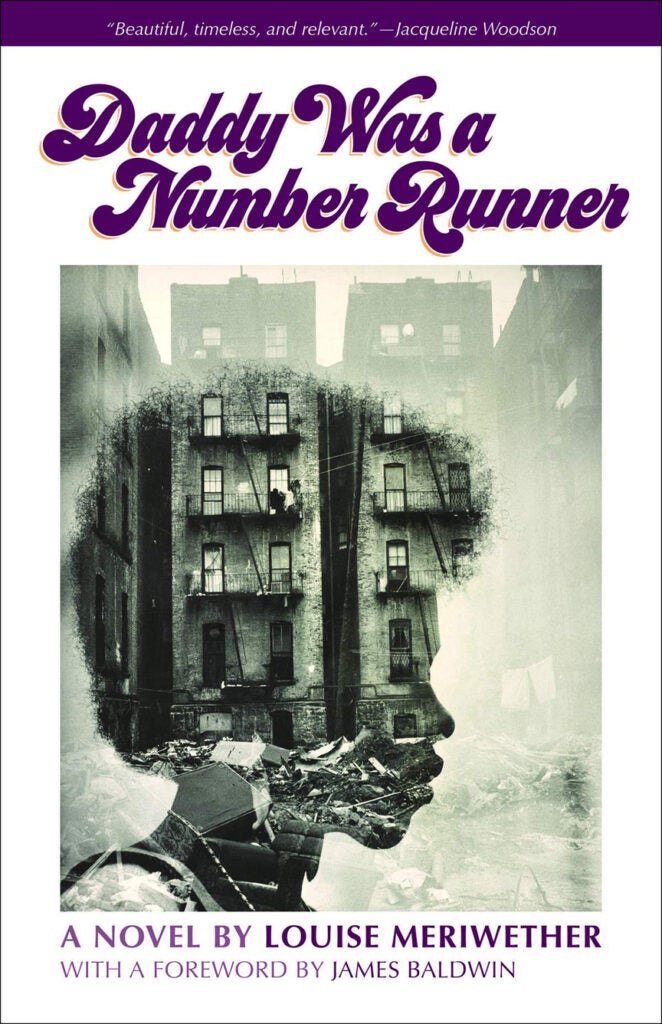

“Daddy Was a Number Runner” by Louise Meriwether

Many names come to mind when people think of seminal authors writing of the Black experience in America — James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston and Ernest J. Gaines. One name that you might not have heard of though is Louise Meriwether.

“Daddy Was a Number Runner” is a book that illustrates the struggles of depression-era Harlem through the eyes of a young girl named Francie. We begin with her helping her father, gathering numbers for a neighborhood lottery that is run by a local gangster and the police.

Her youth and naiveté bleed through the pages as you follow her around the small world she inhabits, trying desperately to live the life that she has to live. Children make up the majority of characters in this book, detailing their daily interactions and the weights they are already having to bear.

In these children lies the beating heart of this classic book. Forced to grow up before they can be children, there is no room for innocence or joy. They are expected to be children while living in a world that requires them to act as adults. The small comforts that slip through the cracks into the hands of the cast are only reminders of a life that they are unable to lead. The adults try as hard as they can to relieve the burden, but they themselves are already broken down, having grown up the same way.

Meriwether pulls no punches, painting a detailed picture of poverty and danger that surround Francie. Her siblings try to protect her, but must also fend their own way and do what they can to make sure that they are not left behind as well. The family structure itself, while intact in the beginning, is pressured from all sides despite the best efforts of everyone in the small apartment. We learn of their hopes and dreams while we watch them lose grip on the very same.

I was very surprised that this book seems to be a side note when compared to others of the same pedigree. While considered a modern classic, it is simply lesser known and celebrated. It should surely be included in any discussion of literature about the history of African Americans in the 20th century, specifically Harlem. It is both a beautifully written book and one that breaks your heart on every page. It perfectly expresses the pressure that bears down on this community and the outside forces that precipitate it.

— Review by Ernie Dixon, Paul Sawyier Public Library

“A Town Called Solace” by Mary Lawson

Set in the 1970s in a small town in Ontario, Canada, we are introduced to 7-year-old Clara who’s keeping a vigil for her sister, Rose. Rose ran away from home after a fight with her mother and has not been heard from in weeks. Clara is also missing her next-door neighbor, Elizabeth Orchard, who has been admitted to the hospital.

Clara checks on Mrs. Orchard’s home every day and is diligent in her duty, which also includes feeding Moses the cat. It is a big surprise when Clara sees a strange man moving into Mrs. Orchard’s house. Eventually, she discovers that her dear friend and neighbor passed away and left her home to the man — someone who was very special to her many years before.

Each of these characters face difficult challenges. How they interact is the story. The bond that the three characters share is slowly unfolded as you, the reader, work through the layers of grief, regret and finally understanding. This book is a gentle read, warm with humor and humanity. Highly recommended.

— Review by Paul Sawyier Public Library staff

“The Hummingbirds’ Gift: Wonder, Beauty and Renewal on Wings” by Sy Montgomery

Those of us who feed them refer to them as “hummers.” They arrive in Kentucky around Derby Day and are one of the final bird species to migrate south in September. Watching them can be a challenge, as they can fly so fast you often only hear the hum of their wings rather than see them.

These are the lightest birds in the sky ranging from the Andean giant that is 8 inches long to the Bee hummingbird of Cuba, which is only 2 inches long. But, what they lack in size, they more than make up for in flight. They alone can hover, fly backwards and even fly upside down.

Sy Montgomery has gone beyond backyard birders and has written about a hummingbird rehabilitator, Brenda Sherburn Labelle. Her specialty is rescuing chicks that have been abandoned. She describes the orphans as “little bubbles fringed with iridescent feathers–air wrapped in light.” With feet as delicate as thread, she carefully coaxes them into one of the many nests she keeps along with her feeding syringes. The hummingbird uses spider silk to make a nest so that it can expand as the birds grow.

Montgomery shares the story of two baby Allen hummingbird chicks, which Brenda nurses with her syringe every 20 minutes. She keeps a magnifying glass near the nest to help her with their feeding.

As their feathers fill in, Montgomery observes that their feathers reflect light like mirrors. And in the shade, the hummer may actually appear to be black. This trait helps protect the birds when in the nest.

The goal is to be able to release them into the wild. But first, Brenda must teach them about flowers and help them cope with older birds. Hummingbirds are thought to be highly aggressive, but Montgomery twists that fact and believes each bird thinks that every flower belongs to them alone. Tension is created as the Allens become accustomed to the wildflower yard. But Brenda is prepared with many extra feeders to allow the older birds to be occupied while the Allens learn the ropes.

Montgomery has written a short, beautiful chronicle on these fascinating birds. She has said that if these orphans can be rescued, perhaps mankind can also heal our planet. Hope you get to hear and see a few hummers before they head south.

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“Harriet the Spy” by Louise Fitzhugh

Published in 1964, Harriet the Spy has been called a milestone in children’s literature. Judy Blume said reading Fitzhugh’s novel confirmed that she “wasn’t the only one who wanted to tell stories about kids who were real.”

Harriet is a privileged 11 year old living on the upper East Side of Manhattan. Her favorite game is one she invented called “Town.” “First, you make up the name of the town. Then you write down the names of all the people who live in it. You can’t have too many or it gets too hard. I usually have twenty-five. Then when you know who lives there, you make up what they do.” Sounds like the beginning outline for a novel.

Harriet wants to be a writer when she grows up, and “Town” becomes the inspiration for her to keep a notebook. Her nanny, Ole Golly supports Harriet’s dream and encourages her to write.

Harriet creates a “spy route” in her neighborhood and writes about classmates, her friends and her neighbors. Unfortunately, Harriet uses real names in the notebook, and is not only observant but bluntly honest, writing awful opinions about everyone.

Then, crisis comes in waves: Ole Golly plans to leave the family and worst Harriet accidentally loses her notebook. Others at school find it, and read what she has observed and what she thought of them. Her friends can’t believe she could be so evil. They want revenge.

How can Harriet cope with the chaos created by the lost notebook, especially without Ole Golly’s support. How can Harriet find a way to fix her life and restore her friendships?

Words have consequences. They have the power to hurt, but they also can heal. Harriet does find a way to make amends by following some advice from Ole Golly.

I first read this novel in college in a children’s literature class, and right away thought this is the novel I wish I had read when I was 11.

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books