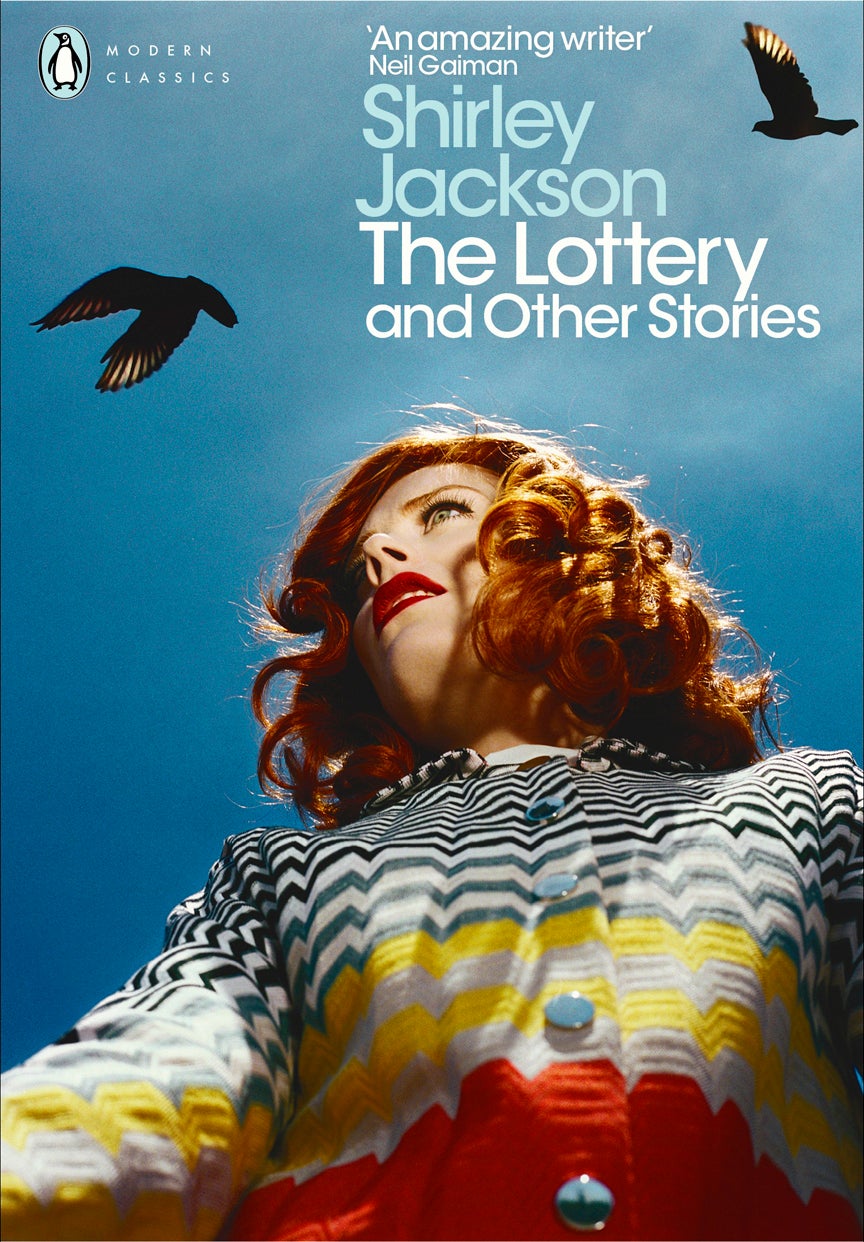

“The Lottery and other stories” by Shirley Jackson

“Perhaps more than anything else, the horror story or horror movie says it’s okay to join the mob, to become the total tribal being, to destroy the outsider. It has never been done better or more literally than in Shirley Jackson’s short story ‘The Lottery.'”

— Stephen King

“The Lottery” was published in the New Yorker in 1948, and since then, has become one of the most recognized short stories in American history. Each year, a small village comes together to hold a lottery, and the “winner” is then stoned to death. As an early example of dystopian fiction, it resonated strongly with the public, eliciting a flood of mail from readers.

Reactions varied from anger to fear to praise, with many readers demanding to know more about the story and why this ritual seemed to take place. What sort of society could possibly allow something like this to happen? Why does everyone seem to be OK with this sort of gruesome violence? What is the meaning of all this?

Writing short stories is difficult because their very nature is one of transience. Unlike a novel, you are placed into a world for a very short amount of time, and it is the author’s job to try and impart their vision to you under this restriction. Questions are going to be left unanswered, and so it is important that readers are left asking the right ones.

“The Lottery” is an elegant example of this, making readers question the violence and absurdity of the situation so that they may question the violence and absurdity that they find in the realities of society. Readers find their own meaning when they are forced to ask themselves “what exactly is happening here?”

And while “The Lottery” is a great story, this collection by Shirley Jackson is filled with other glimpses into different lives that will also leave you with questions about your own. Many of her stories project a desire to escape, of being trapped in a world that seems to leave contentment for everyone but the narrator.

Many are women who seem unsure about the lot that has been assigned to them in life, and wondering if they have the desire or courage to simply live the way that they themselves wish. They are not quite horror or science-fiction, like “The Lottery” or “The Haunting of Hill House,” but they still give a sense of unease and anxiety that quietly bleed off the page.

Shirley Jackson herself was trapped by fear and anxiety, eventually passing away at only 48 years old. The distress which comes through her work was a mirror of her own, and like many great artists, her pain was a conduit for her brilliance on the page.

This book of short stories is a superb example of the genre. For anyone that is a fan of authors like Raymond Carver or Stephen King, these stories will find a place to grow in you.

— Review by Ernie Dixon, Paul Sawyier Public Library web technologies librarian

“Ghost Summer” by Tananarive Due

This anthology of 14 short stories and one novella take us to Gracetown, Florida, a small town with supernatural happenings. Ghosts, werewolves, spirits and shape-shifters are used throughout these horror stories in scenarios that often times feel a little too real.

Due uses ghosts to bring past and present together and shape shifters to show how we can transform our inner selves. Death is really the main character in these stories.

What is interesting about this collection is the way Due divided the stories into sections so each story relates to the other in some way. For this reviewer, the story “Ghost Summer” was the most compelling. In fact, the entire Gracetown section of stories was a great read.

If you are a lover of ghost stories, suspense, horror and apocalyptic fiction, then this book is for you!

Due won the 2016 British Fantasy Award for this short story collection.

— Review by Paul Sawyier Public Library

“The Alice Network” by Kate Quinn

Would it be possible for a female spy during World War I to be successful if she was youthful, innocent and had a stutter? It seems that Kate Quinn is quite able at blending historic facts into a fictional account of what might have happened.

Eve has volunteered for the war effort doing office file work in London. She handles the position well despite her stutter when she is noticed by a superior. He bates her with a German inquiry and she responds in German. Her multi-language skills along with her youthful appearance make her inconspicuous, but the stutter adds to her innocence.

Eve is sent to work with a team of female spies in France, called the Alice Network. Some of the women carry messages successfully hidden in their clothing while crossing the border to the allies. Eve obtains work as a waitress in a restaurant where the German officers dine and drink. As their evenings progress, Eve is able to note specific details of their conversations involving planned missions. But there is a price to pay when her employer notices her hyper-attentiveness.

Quinn alternates this story of Eve with an American college girl, Charlie St. Clair. Charlie’s story takes place in 1947. She is searching for a beloved cousin, Rose, who possibly worked with the French Resistance. It is discovered that Rose worked for the same employer as Eve. Both believe that the restaurant owner is still alive, and that he is the villain they both seek.

Though the two plots are told separately, they do converge in Charlie’s story. The story is gripping, and crackling with suspense. We root for Charlie, and hope for Eve’s safety.

Quinn’s “afterword” is worth reading beforehand. She documents the roles that females played in obtaining critical information about the Reich’s plans in France. The Alice Network was real, and Eve’s character was awarded numerous medals of recognition by the French government.

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books

“Finding Dora Maar: An Artist, An Address Book, A Life” by Brigitte Benkemoun

It all begins with the search to replace a lost diary. He wanted the same size, the same smooth leather, a soft sheen. The clerk at the store said it no longer existed and perhaps they could make do with full grain or crocodile. But it had to be an exact replica of the one he had. They found one on eBay. But when it arrives with the diary pages removed, she notices that the address book was still intact.

Thus, begins the detective work to identify the previous owner.

The address book listed quite a few notables from Paris — Braque, Breton, Cocteau and Chagall. Then there were the first names only listings. Perhaps the owner was close enough to these that last names were not necessary. So, who was this ghost from the past, and what was the connection to listings?

Benkemoun systematically researches every name, eventually tying them all to Dora Maar. Her real name was Henriette Theodora Markovitch, but her friends called her Dora. She was a French photographer, poet and painter, but best known for being the muse for Picasso’s painting of the “Weeping Woman.” Her work was radical and inspired the surrealists including Breton. Jacqueline was one of the “first name only” contacts. Benkemoun discovers that she is Jacqueline Lamba, Breton’s wife.

The one name not in the address book is Picasso. Benkemoun speculates that Dora had copied most of the names from an older address book purchased after she had left Picasso.

Even though there are no papers left from Dora’s life, Benkemoun carefully researches the names from Dora’s world to paint a picture of her life.

Should you appreciate detective fiction and have any interest in art history, this is a gem that all begins with the unidentified owner of an address book.

— Review by Lizz Taylor, Poor Richard’s Books