The enactment of laws to segregation of African Americans from Caucasians is generally refereed to as Jim Crow legislation. The term “Jim Crow” originally signified a dance performed by black-faced minstrel players. In 1860, Kentucky had a population of 1,155,000, of which 236,00 were slaves or free Blacks. In 1900, Kentucky had a population of 2,147,000, of which 480,000 were African Americans.

In 2020, Kentucky had a population of 4,505,836, of which 536,229 were African American. Kentucky’s African American population thus has fallen from 1 in 5 in 1860 to 1 in 12 in 2020.

The passing of the XIII, XIV and XV Amendments to the United States Constitution immediately after the Civil War had little effect in bettering the lives of African Americans in Frankfort. Discrimination and segregation of African Americans wishing to ride public transportation continued within the Commonwealth. Sometimes the discrimination and segregation were exercised by providers of public transportation based on community values while at other times due to local laws.

In July 1870, Kentucky’s discrimination in providing public transport to African Americans became known nationally when U.S. Sen. Hiram Revels of Mississippi was ejected from a Louisville Citizen Railway horsecar. At this time, the Louisville City Railroad Company allowed African Americans to ride in the rear of their horsecars. The Central Passenger Railway Company allowed African American females to ride in the rear of their horsecar and African American males to ride on the horsecar’s rear platform. The Citizen Passenger Railway Company allowed African American women to ride in the rear of the horsecar, but African American men were not allowed to ride on the horsecar at all.

On October 30, 1870, three elderly African American men boarded a Louisville Citizen Passenger Railway Company car and offered to pay their fare. They were refused ridership on the car and, when they refused to leave, they were arrested. The case was tried in front of Judge J. Hop Price of the Louisville City Court. Although the three African Americans were defended by two white attorneys, the three were found guilty of disorderly conduct and fined $5 each, with Judge Price ruling that common carriers could regulate their passengers.

The case was appealed to the U.S. District Court and on May 11, 1871, the U.S. District Court set aside the verdict. The resulting win in U.S. District Court, however, did not change discrimination on the Louisville horsecars or within Kentucky. Bands of White rowdies took it upon themselves to evict from the horsecars any African Americans they found riding on them. However, as a result of protests from Kentucky’s African American communities, race segregation enforcement on horsecars and later on the electric streetcar lines ebbed and flowed.

The passage and signing of the United States 1875 Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination providing public accommodations and in the selection of juries, did little to change the way Kentuckians viewed their fellow African American neighbors. While the provisions of this law banned local acts that resulted in segregation and discrimination of African Americans seeking to use public transportation, these provisions of the federal law were ignored by the white citizens of Kentucky.

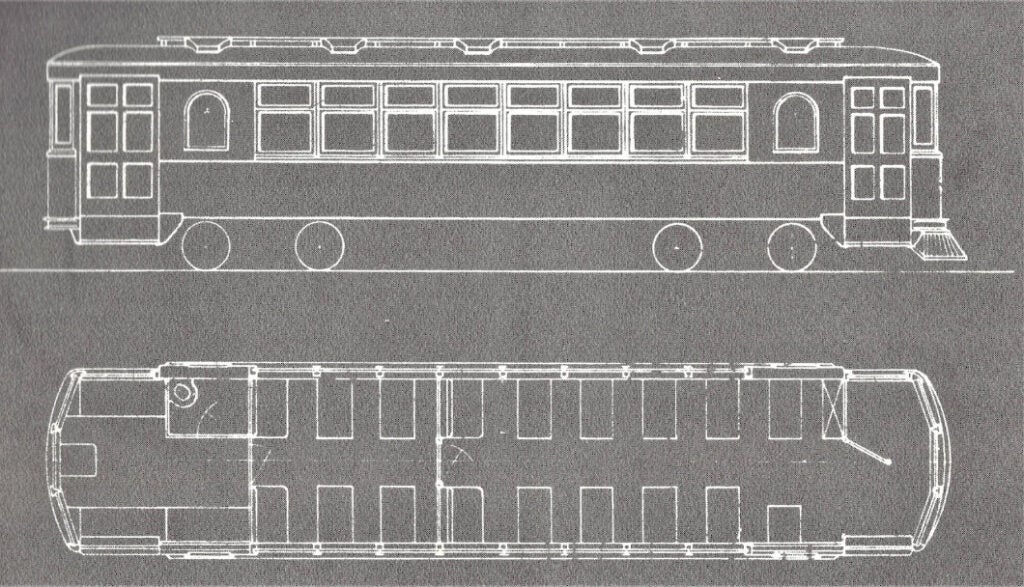

During the 1880s, many local laws were passed in Kentucky regulating ridership on local public transportation. Then in 1892, the Kentucky legislature enacted the Separate Coach Law. This law stipulated that all passenger trains operating in Kentucky had to provide separate coaches for white and “colored” passengers. This law resulted in a challenge to its constitutional legality in Federal District Court.

On June 4, 1894, Judge John W. Barr ruled the law unconstitutional and voided its enforcement. However, in 1900, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of Kentucky’s Separate Coach Law for all public transportation within the Commonwealth. Thus, across Kentucky almost all streetcar and interurban service became segregated. Only those streetcar lines crossing from Kentucky into West Virginia, Ohio and Indiana were exempt from Kentucky’s Separate Coach Law.

However, in 1920, even those exempt public transportation operations came under the Separate Coach Law when the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the Separate Coach Law to be applied to both interstate and intrastate public transportation serving Kentucky. Therefore, in Frankfort during the first half of the 20th century, ridership on its privately owned streetcars and buses was segregated by race. This was also true of ridership on the interurban cars of the Kentucky Traction & Terminal that ran from Frankfort to Lexington. Also covered by this ruling were the passenger cars of the three railroads serving Frankfort — Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, Frankfort & Cincinnati Railroad and Louisville & Nashville Railroad.

The 1950s saw the beginning of a change in the enforcement of segregation on public transportation. In 1954, Rosa Parks refused to move to the rear of a bus that she boarded in Montgomery, Alabama. Her arrest led to a national protest, which resulted in a 1955 Interstate Commerce Commission ruling that Kentucky’s Separate Coach Law did not cover interstate movement of passengers by railroads and buses.

In 1966, the Kentucky Legislature, bowing to public opinion and to be in compliance with the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964, repealed the Commonwealth’s Separate Coach Law. By this time, however, all local streetcars, horsecars, trolleys and interurban operations within Kentucky had ceased operation, but their successors, the local and long-distance bus operators, could no longer provide segregated bus service.

Thereafter, an African American living in Frankfort could sit where he or she wanted on both locally or long-distance buses serving Frankfort.